An upper-class dinner party takes a dark turn when the guests suddenly seem unable to leave the sitting room. There is no physical barrier blocking them; some other power is holding them back every time they approach the threshold. Over the following days of compulsive confinement, base instincts break through the thin veneer of civilization as the guests try to make sense of a situation they don’t understand, struggling for survival like castaways on a desert island. Some succumb to superstitious delusions and feverish hallucinations. Others turn into murderers or rapists. While a black bear and a couple of sheep roam the empty mansion—preemptively abandoned by the serving staff, who suspected something strange was aloft—life outside goes on as normal. The authorities simply cordon off the entrance gate and mark it with the yellow flag indicating contagion.

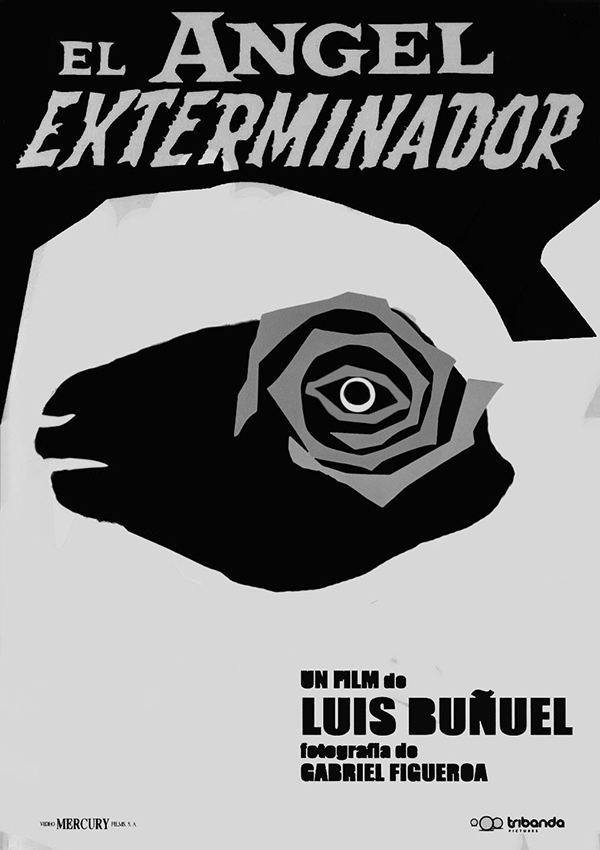

This is the eerie premise of The Exterminating Angel, the film that my course syllabus happened to have scheduled for the weekend my students, much like the servants in the movie, spent hurriedly packing their bags to make it out before the curse hit the Oberlin campus. A week later, Ohio had declared a state-wide lockdown in response to COVID-19. The surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel (1900-1983)—who shot the film in 1962 in Mexico, where he lived as a political exile from Franco’s Spain—was known for his disturbing practical jokes. He couldn’t have come up with a better way to mark the weird and unexpected transition from in-person classes to a second module in which we’re teaching and learning in a state of forced confinement while the world is sliding into another Great Depression.

The idea to dedicate my senior seminar this spring fully to Buñuel’s work and its legacies occurred to me over a year ago. Even then, it felt like a risky proposition. What interest would these films have for students born a full hundred years after the surrealist filmmaker? The challenge, I feared, was not just the idea of teaching modernist cinema to young adults to whom even postmodernism feels ancient. It was also that a steady, semester-long diet of Buñuel might prove too much for a generation that tends to associate learning with comfort in the classroom—and is conditioned to interpret its absence as a personal offense that warrants righteous anger. Was I digging my own grave? How would my students react to the prominent presence of sexual violence in every one of Buñuel’s films, or his fascination with desire in all its forms? And would they be able to bear his stubborn refusal to allow for any sort of hope? I was pretty sure they would enjoy Buñuel’s portrayal of the bourgeoisie—in Spain, Franco, or Mexico—as deluded, hypocritical, and depraved. But I was less certain how they would feel about the fact that his peasant and working-class characters have no redeeming qualities to speak of, either.

On the other hand, I thought to myself, my students’ relative vulnerability would make them a perfect audience. After all, if Buñuel had a single goal throughout his career, it was to use the power of cinema to make his audience uncomfortable. Every single one of his films seeks to disorient viewers, to undermine their beliefs about the world, humanity, religion, morality, sexuality, desire, and themselves. Worse, Buñuel’s movies seem to invite interpretation only to then stubbornly resist it, taking the notion of the tease to a whole new level. As he liked to say: “Nothing in this film means anything.” That’s not exactly a promising point of departure for a class discussion of any kind.

If I’m honest, my doubts were probably less about my students’ potential unease than my own ability, or willingness, to deal with that discomfort. To my embarrassment, I have become noticeably more conservative in my selection of readings and viewings than I was when I started teaching twenty years ago. And although some of that conservatism stems from my increased awareness of my own gender, ethnicity, and age, I know I am not the only one who has become more wary of the hurdles we face when we teach controversial texts and films—and the trouble we may get into, given administrators’ abject willingness to sacrifice the faculty and their academic freedoms to protect an institution’s reputation.

But then, as those things go, I thought: What the hell, and wrote a syllabus for a Spanish-taught seminar that subjected my students to about twenty of Buñuel’s films—from An Andalusian Dog (1929) to That Obscure Object of Desire (1977)—and half a dozen features by self-confessed admirers of his work, from Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch to Guillermo del Toro, Pedro Almodóvar, Woody Allen, and Alice Rohrwacher. The first week of classes, I was more nervous than usual. Now, three weeks from the end of the term, I’m beginning to think my worries were misplaced.

Still, it’s been a semester full of surprises. First, to my bewilderment, the seminar overenrolled. Second, a short survey on the first day of classes indicated that not a single one of my 17 students had seen any of Buñuel’s films before signing up for the course—not even Un chien andalou, the iconic, 16-minute short he wrote and shot with Salvador Dalí in 1929. But as the semester got underway, the real, enduring surprise was my students’ growing enthusiasm and appreciation for Buñuel’s work and the ideas that informed it.

To ease into the subject matter, I’d started them out with two of the later French films (the Oscar-winning Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Phantom of Liberty) before confronting them with the eyeball-slicing, child-executing kicks to the shins that are An Andalusian Dog and The Golden Age. My students were predictably critical of what they saw as the normalization of sexual violence in all four films. But they were also fascinated and exasperated precisely to the extent that these films defied all their attempts at understanding—and therefore preempted the type of normative judgment they’re used to passing in humanities classes. (A type of judgment that Buñuel himself ridicules in the faux documentary Land without Bread, from 1933, which was next on the viewing list, and which destroyed any faith my students had ever had in the documentary as a genre.) By the time we got to Los olvidados (1950), the Golden-Palm-winning masterpiece about young street kids in Mexico City that put Buñuel back in the global spotlight, the class was ready to meet him on his own, treacherous turf.

In mid-March, when COVID-19 threw the semester into disarray and exiled my class to Zoomland, we were halfway through the semester and had achieved enough momentum to keep to our rigorous schedule of viewing, debating, and writing even in confinement. The transition from in-person to online teaching, in fact, was remarkably smooth. I expected the irruption of a pandemic reality to relativize the importance of our collective, esoteric dedicationn to the impenetrable work of a long-dead Spaniard. The opposite happened. Six weeks of Buñuel-induced discomfort, it turned out, had been a fitting boot camp for a world that was rapidly turning as surreal as his films. By the time the crisis hit, I noticed my students seemed to have built a new kind of resilience. “I feel I’m appreciating this quarantine differently,” one of them told me. “How linear or logical is time anyway? Why do we insist on analyzing this abnormal reality with normal eyes?” “This whole pandemic could be a Buñuel film,” another said. “He would very much enjoy its ironies. The bourgeoisie have continued to socialize and travel, for example, while the pandemic impacts low-income communities to a much greater extent. And Buñuel would find great pleasure in critiquing religion, as religious ‘devotion’ has become a catalyst for the rapid spread of the virus.”

In Buñuel, there is no normal. Standard forms of morality are in for systematic ridicule. If anything, he shows us to take the world, each other, and ourselves as we are: imperfect, animal, hypocritical, irrational, inexplicable. In the first week of online meetings, as COVID-19 was beginning to ravage New York City and Detroit, we discussed Nazarín (1959), one of several of Buñuel’s films that reveal their protagonists’ misguided attempts to live like saints. (It contains one of the most desolate scenes in the history of the medium: a lone little girl walking through the empty, sunlit street of a plague-ridden village, dragging a white sheet behind her, with death-tolling bells as the only soundtrack.) When Nazarín, a naively innocent priest, offers a woman who is dying of the plague a chance to confess and the promise of entry into heaven, she tells him to scram because she prefers to die, unsaved, in the arms of her lover. So, too, Viridiana, a young, pious novice in the 1961 movie of the same name, ends up crushed by the world (and almost raped by the same beggars she’s attempting to save). In the final, scandalous scene, she nixes her vows in favor of a threesome with her cousin and the maid. “Saints,” George Orwell wrote, “should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent”: “The essence of being human is that one does not seek perfection, that one is sometimes willing to commit sins for the sake of loyalty, … and that one is prepared in the end to be defeated and broken up by life …. No doubt alcohol, tobacco, and so forth, are things that a saint must avoid, but sainthood is also a thing that human beings must avoid.”

Buñuel’s films are an antidote against all forms of idealism. He “makes the charitable the butt of humor,” Pauline Kael wrote, “and shows the lechery and mendacity of the poor and misbegotten.” It’s impossible “to get a hold on what Buñuel believes in. There is no characteristic Buñuel hero or heroine, and there is no kind of behavior that escapes his ridicule.” I wasn’t wrong to suspect that this would unsettle my students. It did. Still, I underestimated their ability to respect that position and learn from it.

I’d also underestimated their ability to embrace ambiguity. Because for all its ridicule of idealism, Buñuel’s work is also a remarkable example of moral, political, and artistic commitment. Spending a semester in his company—and of those, like the young Italian director Alice Rohrwacher, who follow in his footsteps—has been enough for all of us to discover, or rediscover, the sheer power of film. It’s a potential that tends to remain as underused now as it was in 1953, when Buñuel gave a rare lecture at the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Film, he said then, can be an “instrument of poetry, with every sense that term may contain of liberation, of subverting reality, of an opening to the marvelous world of the subconscious, of inconformity with the narrow society that surrounds us.” Cinema’s power is awesome, Buñuel said. It can “make the Universe explode.” But, he added sarcastically, “for the moment, we can rest assured.” For “in none of the traditional arts is there such an enormous gap between potential and fulfilment.”