The title of Alice Neel’s major retrospective, “People Come First,” says most everything about the artist and indeed the current spirit of our time. An early populist painter in the 20th century, Neel meticulously recorded the poor and disadvantaged colorfully and accurately. But it is also fair to say that her paintings can be one-dimensional and, in the later part of her career, even superficial. It is a romantic vision that animates her art, which rightly celebrates New York Cit’s racial and ethnic diversity, a point of view she lived by–Neel worked and lived for 24 years in Spanish Harlem, recording its inhabitants with true sympathy. Yet her romanticism, of a bohemian sort, may misread the darker aspects of racial prejudice and neglect by virtue of an outlook that might be described as decorative or overly idealized (this does not happen in Goya!). It is true that her leftist political outlook, genuine in nature, was active during the course of her life, but Neel’s preoccupations may have resulted in an elevated vision of suffering, surely not the case in actuality.

Still, her vision indicated the classic stance of the best of a progressive sensibility: an empathy for people, no matter their economic, racial, or ethnic background. (By comparison, the young, gifted black artist Amy Sherald also makes paintings that celebrate black people from everyday life; like Neel, she demonstrates a determination to do away with social status in work that evokes the dignity of people from real life.) Given Neel’s will to render the spirit of the poor in their best light, we can and should be sanguine in regard to her optimistic treatment of American lower classes (she also painted persons from higher social strata). We must remember that when she was working, the United States was not known for its sympathies toward the economically vulnerable. She belongs to a particularly successful American vision, more middle-brow than high–in writing, the novelist John Steinbeck comes to mind. Because today art is driven strongly by a determination to democratize culture, Neel’s bias looks, more than ever, prescient and enjoyable–nearly the triumph of life over culture. In this particular sense, Neel was entirely successful, fulfilling completely her sympathies for our underclass.

Indeed, Neel is so good at what she does that she embodies the American art world’s current wish for a cultural Marxism, in which fine art should serve the need, actually the necessity, for a completely level cultural milieu. One can debate the desire in the sense that, historically, much of the best art regularly was produced within hierarchies supported by an aristocracy. But that was then, and this is now, and we must be fair, in our reading of Neel, to her spirit and that of her time. Maybe it is right to say that her sympathies (like those of the poet Allen Ginsberg) linked Neel to an inspired reading of popular culture. Her art is marvelously accessible, being rich with personality, which she renders with genuine emotional force. New York became her muse, enabling her to paint all manner of people–leftist colleagues, people from the artworld, writers, depictions of life among the disenfranchised. Early on in Neel’s body of work, her sympathy and emotional directness come through, making her an artist of positive feeling, even among people who had little or nothing in life. Her insistence on what we can call the essential goodness of people, no matter their circumstances, made her art particularly enticing. It is work that asks the viewer to internalize an optimism despite the great social suffering Neel lived through and depicted–the great Depression, the Second World War, the intense conflicts, social and political, of the Sixties.

In light of what the American artworld professes today, we can easily admire Neel’s steady regard for the poor. Even so, we can also question her technical skills, which, at times, come close to illustration. During the 20th century, we were living in a time of rapid, revolutionary visual innovation, but very little of that comes through in her art–even if a section of the Met’s show deliberately makes a case for abstract qualities in her work. In fact, she was in a traditional painter, someone whose leanings were quite conservative, despite the progressive vision the paintings carried. But, given her goals as an artist, how could Neel work otherwise? Certainly, abstraction would be difficult to use in the portrayal of people, although it can also be said that an artist such as Picasso regularly, and more than successfully, represented people via a mixture of figuration and abstraction. But when Neel was coming of age in America in the 1930s, there was a good deal of politically biased, representational art being made. It is likely her values, social and visual, were determined during this period. She never gave up on giving her sitters the same empathic treatment, no matter who they were. This means, though, that a certain sameness of effect creeps into her art, perhaps robbing it of depth.

The idealization of the figure in art is historically based–we think at once of the grand, even grandiose, but very great figures in Michelangelo’s art. But this does not mean that idealization always maintains a high import; sometimes it simply rides the surface, and lacks discernment, turning the figure into someone mock-heroic. Neel’s idealism is genuine, but sometimes shallow, being the result of a superficial painterly approach, which can be remarked on especially in the later work. Is there such a thing as an illustration capable of communicating sorrow and suffering? Neel’s life was not without hardship; she was without money, she suffered psychologically and had a nervous breakdown early in adult life. Yet her portraits can read the character of her sitters rather lightly. How does one attain a visible depth in the painting of people? It is a difficult question, not easily solved. Instead, in the 20th century we have the problematic style of Socialist Realism, most visible in Russia and China when they were devoutly communist. The idealization is clear, but so extreme as to lose contact with the reality the work was trying to express. Maybe this happens at times with Neel’s art.

French Girl (1920s), a very early work, was likely made when Neel was an art student in Philadelphia. Done mostly in browns for the sitter’s ample blouse, short hair, and background, with a dark tan used to express her face, French Girl is a classically inspired painting, influenced by the American painter and teacher Robert Henri. Yet even while Neel was just beginning, one senses a close attention paid to the personality of the subject; Neel places her focus on the girl’s face: the girl’s expression is quietly lively despite her staid pose and the muted color used to record her features. It is clear from this painting that Neel was educated very well in an academic sense. There is no sense of the liberated style that would overtake her sensibility as time went on. In 1935, when Neel was participating in the bohemian circles of New York, the portrait of the Marxist poet and essayist Kenneth Fearing appears. It is a complex image, taken as much with the city itself as with the writer; we see, at the top of the painting, an elevated subway train, lit from within. Beneath the train is a green metal entrance to the subway underground, and at the bottom of the composition, we see a number of poor walking on the sidewalk, with a lifeless man lying in pools of blood. Fearing himself is painted in highly sympathetic terms. Thin, with an angular face, he wears glasses and reads a book.

On the left side of Fearing’s chest, Neel painted a skeleton with blood pouring our from its bones. It is a bleeding heart, a sign of his empathy for the world’s suffering. It was a time when a bleeding heart could be painted without irony. Now political narratives are often treated in art theory, which abstractly addresses the ongoing problem of struggles of the poor. At the time, Neel risked no accusation of sentiment, and the painting ably documents a noted politicized poet. Neel, who was born late in January 1900, had reached the age of 35 years when she created the likeness of Fearing, so this is a painting done in the beginnings of mid-life, when the artist had made decisions about her beliefs and was in command of the skills she possessed. Her capability for empathy, always her greatest strength, is evident in this moving portrait of someone committed to the left and to literature. It is good to remember that this period was free of excessively romantic considerations of the poor in art; the time was devoted to the hard recognition of the continuing troubles of minorities and immigrants. Neel’s portrait of Fearing can be seen in this light.

Neel was also unconventional on a personal level. In 1924, in a summer school affiliated with the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, she met the Cuban painter Carlos Enríquez, whom she would marry a year later. A 1926 portrait of the artist shows him as a thin, highly romantic figure, wearing a gray coat and a floppy bow tie. Self-contained and proud, Enríquez sits at a table with a slender glass filled with alcohol–every inch the painter. According to exhibition notes, the painting was likely made in Cuba during the couple’s trip there in 1926-27, where Neel first presented her paintings in public. One hesitates to speculate, but it may be that this early romantic connection with a foreign artist would orient her toward her gift for painting people from other backgrounds.

Romantic preoccupations aside, Neel maintained her interest in politics from the start. In the 1936 painting, Nazis Murder Jews, the artist depicts the May 1st Marxist parade of that year in a darkly toned painting. In the front are four artists from the Work Projects Administration, one of whom carries a placard with the words of the title written in black. The procession extends far back into the distance, giving a sense of the more than 40,000 who walked in favor of progressive causes and the recognition of German anti-Semitism. Only a few red banners stand out in the background. This is an overtly political work of art, but Neel was likely best at the implied politics of her perceptions–for example, when she painted the impoverished minorities she lived with in Spanish Harlem. She did so mostly without idealization. In Two Girls, Spanish Harlem (1959), two young black girls (daughters of a neighbor), maybe five years old, gaze back at the viewer, their look filled with innocence and unspoken feeling. Yet their presentation is hardly sentimental. Here Neel merges her affection for the disadvantaged with a realism that takes the circumstances surrounding these children into account. A good deal of Neel’s attraction as a painter stems from her unflinching account of poverty, as well as her clear approach toward her subjects.

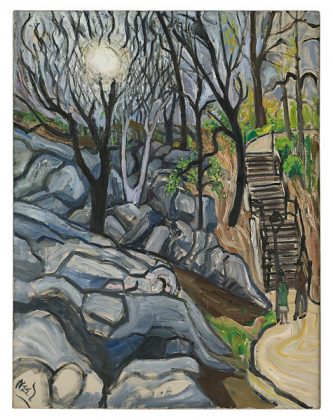

In Central Park (1959), Neel records, in a style not unrelated to the American realist Charles Burchfield, a bucolic scene in the midst of Central Park, Manhattan’s great green space. On the lower left side, we see gray boulders taking up the space, while in the middle and upper right, dark, leafless trees frame a hazy sun. On the far right is a path, part of it steep and requiring stairs, before which we see two indistinctly painted figures. Despite the indications of civilized life, Central Park is a compelling treatment of a landscape whose greatest strength is its author’s appreciative view of nature. Neel also demonstrated her liking for more urban scenes: in the 1968 Cityscape, Neel shows us the straight lines and slight curves of dark streets ploughed recently, with a snow-covered traffic island in the middle of the painting. The island supports a small group of leafless trees; in the upper part of the composition, we see a building with a neon sign, while in the lower left, two cars and a truck appear. The homely solicitude with which Neel works the painting proves again the artist’s affection for New York City.

Indeed, New York City was the backdrop for Neel’s gifted reading of its inhabitants, its architecture, even the bits of nature found in Manhattan. New York remains a site of pilgrimage for the young artist, but life is not the same here as it was during Neel’s time. Today, one needs nearly to be independently wealthy to live downtown, traditionally the home of many of New York’s best artists. Neel, a classically trained urban painter, found a home in New York at a time when it was possible to be a poor artist there. Living in Spanish Harlem, a poor part of the city, enabled her to express her political sympathies quite effectively. Now it is hard to think of any neighborhood in New York that isn’t gentrified; even the South Bronx, notorious for its impoverished state and broken buildings in the 1960s, is becoming the home of artists–and inevitably, gentrification will follow. Indeed, the wealth of the city has become so dominant it is fair to ask whether New York will remain inexpensive enough to support young artists without money. By living the way she did, and painting the way she did, Neel embodied an attitude of political virtue and esthetic independence very difficult to keep alive today.

New York artworld celebrities such as Andy Warhol, whose portrait Neel painted in 1970, and the curator Henry Geldzahler, his likeness rendered in 1967, show that even as Neel became famous, she was not rejecting new ways of making and looking at art. But her style was becoming quite loose; the two men are rendered in a manner close to illustration. Neel’s version of Warhold is a study of the notorious artist sitting in a chair; bare chested, his stitched wound prominent, the artist’s eyes are closed, as if he were in a meditative state. His silver hair is neatly combed, and his hands rest just above his knees as he seemingly contemplates–what he is thinking of, we don’t know. Geldzahler, originally from Belgium, a historian and critic as well as a curator, is rendered more straightforwardly: he sits in a tall-backed chair, his right hand gripping its top edge. Geldzahler wears a long-sleeved purple shirt and brown pants. His countenance radiates calm and a certain satisfaction; Neel pays close attention to the brown glasses and thinning blonde hair of the man, who began the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s contemporary section in the later 1960s.

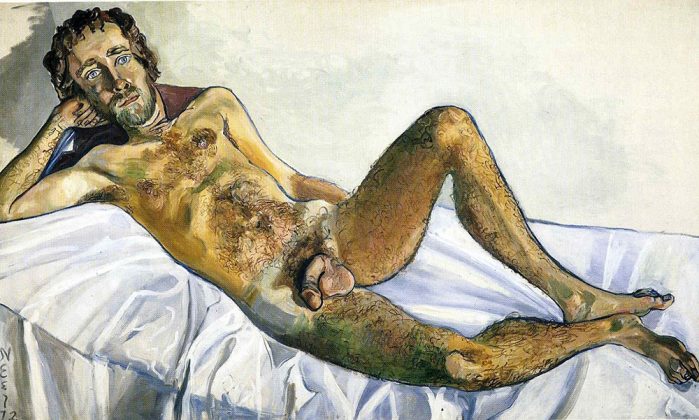

Neel’s art also makes it clear that she was no stranger to erotic expressiveness. There are a good number of nudes in the show, several of them full-frontal treatments of men. The portrait Joe Gould (1933), shows off the uncircumcised phallus and manic stare of a notoriously eccentric downtown inhabitant. There is a picture of the naked man directly facing us in the middle of the painting, as well as studies of his naked body on either side of the composition. His phallus is a center of interest; it is repeated three times in the middle figure. It is a picture of unbridled sexuality in a time of early experiment. John Perreault, a full nude portrait Neel created in 1972, shows the art critic and curator, who was responsible for a well-regarded exhibition of the male nude, in full erotic recline. His bright blue eyes, tousled hair and short beard, are notable for their figurative accuracy, which also applies to his penis. This was the time of the first feminist wave in America, so the directness of Neel’s treatment would have been seen in that light; at the same time, this was not a new occupation for Neel, who had been painting sensual portraits of her lovers for decades.

In light of Neel’s early established political views, as well as her equally early treatment of New York’s poor minority population, it is easy to see her as a social hero. She may be best in her portrayal of women; her pictures of nude pregnant women are very strong. Whether she can be seen as a major art figure occasions more complex debate. Outside of the academic studies she did as a student, Neel demonstrated a certain coarseness of effect. Visual refinement was not part of her vocabulary. Does this weaken her achievement? It is difficult to say. Given the honesty of her outlook, in both private and public life, perhaps concern for her skill should be set aside. Yet it is also true she can be criticized for her lack of technical interest–as Neel said, “People come first”–but then that means that painting comes second! When we look at her art, we tend to emphasize its content rather than admire the way it is painted. Despite Neal’s popularity–and popularity is a regular measure of critical esteem in American art, as happened with Warhol–it is fair to see her as lacking somewhat in ability. This may, or may not, influence our view of her accomplishment.

We need to remember that not only figurative artists like Neel but abstract painters such as Jackson Pollock and the sculptor David Smith took part on the left during the course of their careers. Neel’s ongoing populism, which fits contemporary sentiment so well, should be seen as a historically determined leftist stance. Yet her art is stylistically conservative. Because Neel was never a nonobjective painter, it is fair to look at her oeuvre in light of an art historical awareness–even if she is better known for her socialist leanings. Today, when one’s social practice is perhaps even more important than the work itself among younger artists in New York, a critical view of Neel may seem irrelevant to our esteem. Yet a populist reading of her work may be equally fragmented in regard to our complete reading of the artist. In her late work–Neel lived to be 84–the looseness of the painting may cause us to question our regard for her emotional drive. It is not necessarily a misjudgment to criticize her for her easy accessibility. Still, this is not what Neel is known for. Instead, she is understood as a painter of unusual compassion, whose bohemian life sided with much of the most forward politics of her time. In light of her circumstances she can be seen as someone a bit larger than life, despite her lack of interest in technical achievement.