Miguel Trelles is a mid-career painter and draftsman working on the Lower East Side. Born in San Juan, the artist came to America to pursue his college and professional education. (But he maintains close ties with his native Puerto Rico, where his family resides.) Trelles is an accomplished artist whose studio is in The Clemente, a former public school on Suffolk Street. He is part of the community there, and can be seen as one of the stalwarts of the Latino artworld in New York. The series of questions posed here will help the reader gain not only some sense of Trelles’s esthetic, but also his deep connection to the under-recognized Latino artworld, which functions in New York City on the margins of convention–in showing, in art writing, in collecting–and which, consequently, deserves greater attention.

Trelles is also an administrator at The Clemente, where his activities are strongly oriented toward Latin-American activities; additionally, his paintings now regularly describe both Mayan culture and the Caribbean landscape. But it is also true he has taken a strong interest in Chinese traditional painting; his commentary on this field tells us a lot about our current propensity for eclecticism, regarding which he delivers an informed, complex opinion. His thoughts are wide-ranging and introduce us to his many-sided art, as well as focusing on some of the issues facing contemporary artists from the Caribbean.

Goodman: Please describe your upbringing in San Juan, Puerto Rico. You father, still an active writer while now in his early 90s, reviews film, while your mother writes about Spanish-language literature, novels in particular. One of your sisters studied film at Harvard and now teaches at the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan. How did so cultured and intellectual a family result in your becoming a painter?

Trelles: As my best friend and front-door neighbor Amaral describes, when I was growing up, our seven-member (five-sibling) family ensemble was always at church, the beach, or the movies. At home our parents turned us on to literature; and there were all these movie press kits (photos and posters) and books around the house. On the walls there still hangs a silkscreen print by Myrna Baez (recently deceased and one of our great printmakers), a photo of Paris, a print of Havana, and a beautiful virgin from the Escuela Cusqueña.

I have been drawing ever since I can remember: little figures, fights soon after, then autos and airplanes. But mostly people, especially faces. A fascination with comic books and science fiction/fantasy illustration led me to become somewhat literate about that genre, anticipating my subsequent foray into art history. Because my parents were both humanists in the broadest sense, we were exposed to a lot of writers, filmmakers, and artists, but the writers/critics were the most prevalent among those visiting. Still, a heavy-weight artist friend of my parents, Franciso Rodón, suggested to my parents not to put me in art classes but to just let me do my thing.

Goodman: You went to Brown University for undergraduate studies and to Hunter College for an MFA. For a semester, after college, you studied historical Chinese painting at Yale. How did these experiences influence your art? You have remained in America, living in New York City. Why have you stayed? Is New York City still a place to be an active artist?

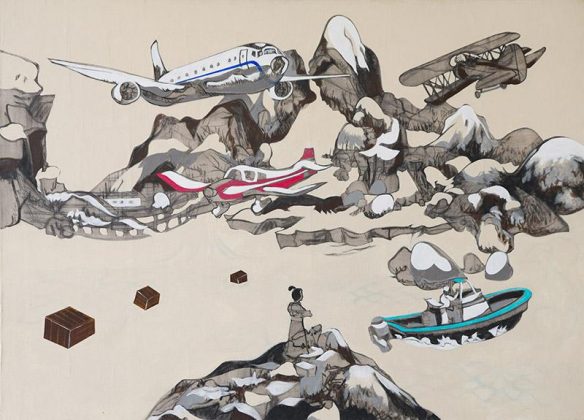

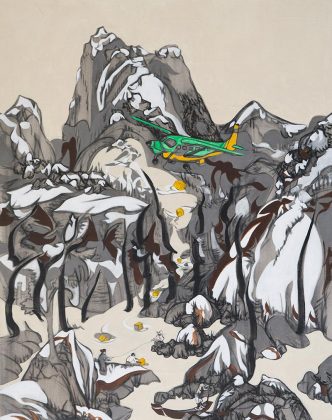

Trelles: I came from a University of Puerto Rico household, so my U.S. experience was unexpected, challenging and inspiring. Upon arriving at Brown, I first heard, “You don’t look Puerto Rican”–some kind of puzzling prologue to my experience in the States. A fellow student, Julia Martin, was instrumental in helping me explore beyond my Caribbean brand of Judeo-Christian, Western cultural assumptions, turning me on to Chinese civilization. Art Department Professor Edwards encouraged me to cross register at the Rhode Island School of Desigen to obtain highly structured painting instruction. At the same time, Professor Bickford shaped my criteria on Chinese painting. At Yale, Mike Hearn from the Met Museum shared actual masterpieces with us. I even met Professor Richard Barnhart, the well-known historian of Chinese painting. This exposure would subsequently transfer my figurations into the “Chino-Latino” series.

I have made New York my home because as a Puerto Rican I feel paradoxically both culturally at home here (the Nuyorican ethos and esthetic are inspiring) and because of the international diversity the city offers.. Perhaps I would have moved elsewhere if Ed Vega, the noted novelist, had not offered me a studio at The Clemente Soto Vèlez Center. Opportunities like this are probably growing increasingly scarce. but if a place like The Clemente can live up to its mission of encouraging and supporting Puerto Rican and Latinx visual artists, we may be able to continue being a part of New York’s cultural milieu.

Goodman: Many, many legal and illegal immigrants–some of them artists–from Spanish-speaking countries now live in New York. As a bilingual Puerto Rican artist, where do you stand in the art community here? Do you identify as being inside or outside the American community? Does your identity play a role in your art?

Trelles: I belong to the Puerto Rican/Latino art community and am glad to show in any space when invited. I am bilingual but, linguistically and culturally, I revel in Spanish. I actually teach Spanish at Baruch College in the city. Because of this and because my upbringing and exhibition travel have exposed me to the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and to Latin America, I easily relate to and am conversant with legal and so-called “illegal” artist immigrants from our America “en español.”

Most important, my association with the Center of Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter has allowed me to research, write, and be published regarding the Center’s splendid Puerto Rican print collection. Additionally, several of my initiatives at The Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural Center have led to the creation of programs meant for Puerto Ricans and Latinos to have a greater presence in the institution. For the past 15 years I have been chief curator of BORIMIX, a very inclusive yearly exhibition promoting the work of Puerto Rican/Latino visual artists while addressing Puerto Rican culture. Still, before any of these associations, however important they may be, my cultural identity is overtly manifest in my printmaking output, which enables me to reflect on and reference the rich Puerto Rican printmaking tradition that spanned the second half of the 20th century.

Goodman: One of the very interesting things you do is to run El Latea, the theater at The Clemente, which is a community-oriented, former public school turned cultural center. You also have a studio there. Can you talk about your role in the organization, and how it has affected the way you work and see the New York artworld?

Trelles: Yes, since 2016 I have been Co-Executive/Artistic Director of Teatro LATEA. As LATEA board members established in writing in 1993, The Clemente’s mission “is focused on the cultivation, presentation, and preservation of Puerto Rican and Latino culture.” Since setting up shop at The Clemente in 1995, I have been an active participant in its history. Since then, I have strived to produce work, and to invite fellow artists and others to join me for a drink and a visit, all the while encouraging Loisaida neighbors, downtown community inhabitants, and the NYC public to attend our exhibitions, initiatives, and efforts.

Ultimately I believe the aim should be to safeguard the Puerto Rican/Latinx ethos within the institution as well as promoting a certain Clemente brand. In addition to my main art-making endeavor and, more recently, my stewardship of the LATEA theater, I have been involved as an activist striving to keep the building from auction. As a board member, I am invested in balancing mission and management. Currently I paint in my studio on the third floor of The Clemente, head the theater, and remain an active participant in the ongoing process to revamp the institution.

Goodman: Despite the considerable number of Hispanic artists in New York, the amount of attention paid them is relatively small. How much of a need is there to develop an infrastructure supportive of Hispanic artists? How can this be done?

Trelles: Even though the amount of attention paid to the considerable number of Hispanic artists in New York is still underwhelming, I am an optimist. Currently, I see two kinds of movements coming up to raise awareness and the prospects for Hispanic artists.

There is a resurgence and dynamic push by existing grassroots arts organizations to provide exhibition opportunities. Some institutions I know of are the Local Project, En Foco, El Puente, Bronx Arts Factory, CCCADI ,and Taller Boricua. Then there is the phenomenal New York Latin American Art Triennial, which is growing and gaining momentum, thanks to partners like the Longwood Art Gallery at Hostos College.

The other movement raising awareness is the Cultural Diversity Initiative, begun in 2015 and initiated by the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs. Its purpose is “to promote and cultivate diversity among the leadership, staffs, and audiences of cultural organizations in NYC.” The leadership issue is incredibly important because a lot of cultural organizations that are making a good faith effort to diversify with shows by Latinx artists and reaching out to Latinx publics do not have Latinx in leadership positions. And then it also has happened that Latinx institutions give top positions to folks who are marginally conversant with Latinx culture.

Finally, there is the “critical” issue of criticism, an issue across the board as we need more and more approachable and direct critical discourse, especially about Latinx art; it would also be important for NYC to have some of it in Spanish as well as English.

Goodman: Drawing is a strength of yours. How did you develop your drawing skills? Would you go so far as to deplore the lack of skill in much of today’s art? Or is that simply a way of concealing conservative feelings about culture?

Trelles: Drawing is the fundamental of my practice. Of course, I tremendously enjoy painting without drawing, and yet I often choose to draw. My flat files attest to a robust output of pencil, chalk, and pen and ink drawings. In meetings, or on the phone or in any situation where I find I have a pencil and a surface, I gravitate toward drawing.

On the subject of skill I believe, after some experience teaching introductory drawing at the college level, that many students are finding a new regard for drafting skills when they encounter an encouraging mentor to help address the challenges and pleasures of mark-making on paper. It must be stressed that few if any students today have as significant and constant an acquaintance with paper (due to digital reality) as did students learning in the 20th century, when paper was still a universal medium.

As for claiming that to deplore the lack of skill in today’s art is “simply a way of concealing conservative feelings about culture,” I don’t agree. But it could be. If drawing on paper can be said to have previously been the tool for “visible” thinking and the conceptualization of architecture, design, and engineering (the basis of so much in our contemporary world), it is true that all that is done digitally today. So the regard for hands-on drawing skills as part of the professional tool kit has significantly diminished. Invariably this demotion has extended to visual art, which has also gained many hands-off two-dimensional tools, where the “craft” resides in the algorithm.

Realizing this, those who may regret that we are on the cusp of absorbing and reflecting the world and our life experience in an increasingly hands-off manner do have broader misgivings than conservative feelings about culture. Ultimately it can amount to taking a philosophical exception to the way world civilization keeps going. Then again, perhaps a balance can be struck, and we can eat machine-processed food still prepared by people, confirming at the same time that an autocad diagram is tremendously enhanced by a few gestural strokes–the result of the hand–in just the right place.

Goodman: I have written on your “Chino Latino” series, a group of paintings strongly oriented toward your interest in scholarly, historical Chinese landscape painting. How did you make the leap from being an artist from Puerto Rico to being an honorary Chinese painter? You have since moved on to other themes and subject matter. Why did you make the change?

Trelles: After being introduced to Chinese civilization, history, and culture in college, and then pursuing Chinese art history, there was a disconnect. After all, many Westerners have expressed their admiration for Chinese civilization. As for an honest and genuine appreciation of the art itself, there can be–and in my case there was–an emotional distance. I wasn’t truly feeling a deep involvement despite my studies in Chinese painting, which could not keep up with my familiarity and admiration for key figures/works of the Western canon and its emphasis on the body. This made the Chinese landscape unpalatable.

Ink drawing transformed my appreciation of Chinese art. I had grown up drawing with ink, and even when the monumental landscapes I was studying seemed very “cold” I couldn’t help grabbing a brush and using ink to try to copy a passage or borrow a texture for something else. And then, learning, experimenting, and becoming a painter, a “fin de siècle Puerto Rican painter” mind you, I was overwhelmed with the question, What to paint? I also needed to face the whole criticality, innovation, and art historical self-awareness problem. I asked myself, Why was landscape in the West relegated to secondary status?

So perhaps the landscape was a subject deserving my attention, especially since, by the mid-Eighties, the destruction of the biosphere was becoming evident, even if this was less commented on then than today. As an artist from the Caribbean, I knew that the whole region is the ultimate landscape attraction. Thus, becoming a landscape painter made sense. And yet, how could the ubiquitous and picturesque shack along the stream become formally engaging? After much looking, I realized that Chinese landscapes could be just as folksy as the Caribbean tradition, only that their scale was far more ample, with a magnitude transcending the minute and the personal. So why could I not be a Puerto Rican scholar painter in the same way a Chinese scholar painter worked? I would paint a Caribbean of the mind.

Goodman: An interesting, new direction for you is the inclusion of Mayan faces and culture. Has this been another way for you to include yourself within the traditions associated with Hispanic culture? Why does Mayan culture interest you so much?

Trelles: The Mayan drawings and some motifs bursting into landscapes and paintings have been the by-product of my experience teaching college students about the culture and civilization of Latin America. Almost always, texts, syllabi, and all else began with a brief mention of the pre-Columbian civilizations. And then we started. . .

I delved into our America’s pre-Columbian history to look at the complexity of the issues and to some extent the continuity of some of those same issues even after the incredible disruption/destruction/reconstruction carried out by Eruopeans. As with my Chinese landscape epiphany, my studies have resulted in a profound engagement. And I have opted for the Maya because I find the ceramic codices and other drawings to relate to some gestural sleight of hand that has some (very limited) parallels with Chinese drawing and because they appeal to me aesthetically (I pick up those comic book echoes). Because the drawings are done with black, and with a very modest palette, they engagingly transmit a very lively court reality.

Goodman: Clearly, you jump from place to place in your imagination. This makes your work highly interesting. But is eclecticism being abused today, in the sense that people feel they can borrow from anywhere and from any culture? How do you see the practice?

Trelles: Well, I imagine I am part of that orientation. But I have gravitated to these cultures almost by accident; I was not really looking for them to make art. As I have learned about them, the fact that I am an artist takes over and leads me to borrow or in my case jump in to fully incorporate a different style or culture. As for the practice of eclecticism, I think on the one hand, Why not?, but on the other hand, I feel it is incredibly difficult to pull off. Many who try eclectic practices, thinking it might be a shortcut to inspiration, might just as well try introspection–it might be faster to achieve esthetic independence this way.

Goodman: There has been a tradition, since Goya, of strong political art in Hispanic painting. Yet your work does not overtly represent a social point of view. How needed is it for artists to be political today, in particular artists of your background?

Trelles: The more overtly political efforts in my work are found in the prints and some drawings. Other than a modest show currently up (but like everything else, totally shuttered) at the Puerto Rican Family Institute on 14th Street, I really have not had a good opportunity to show my prints.

As for the paintings, particularly the “Chino-Latino” series, I do believe it is political by invoking the landscape at a time when we are getting closer to totally destroying it. And yet, I favor a less overt and more subtle political commentary as there has been a surfeit of political art that doesn’t allow the viewer to think or consider the terms and arrive at a conclusion. This kind of work, agitprop really, whether from the Hispanic or any other tradition, does not appeal to me.

But, even so, prints calling for rallies and marches–that sort of advocacy–are the way artists of my background can join and assist in pushing for the transformations that need to take place for a more equitable and eco-friendly world society to take hold.

Goodman: Please name another area of interest in your art. Figuration plays a major role in the way you work. Why have you turned away from abstraction? Is it mostly a matter of temperament, or is it a deliberate choice?

Trelles: I like abstraction; it’s just there’s a limit to how much one can branch out. Also, with abstraction I sometimes get scared with how the formal takes over. I like to see a story or, even better, to have it evoked or hinted at. Sometimes I think that further down the line I’d love to tackle pattern and figure out if it would be at all possible to play with/subvert that tradition. Potentially I’d look to combine Escher and Agnes Martin. . .

Goodman: In the next five years where do you want to be as an artist? Do you still want to work in New York City? Do you think there will be, eventually, a true place for a gifted painter like yourself in this city?

Trelles: In the next five years I’d like to be in The Clemente Center with more Puerto Rican/Latinx artists to share my painterly/cultural efforts, and to have a bit more financial security, so I could spend more time in Puerto Rio with my family. I don’t know if eventually there will be a true place for me in this city, but I’ll be honored to have my place.