Ema Rosenstein was born in Lwow (now Lviv) in 1913 and died in Krakow in 2004. In between, she survived the Second World War as a person of Jewish heritage; she had the terrible misfortune of seeing her parents murdered in the Polish woods and was herself wounded but was able to escape. A leftist by temperaments, she joined artists’ organizations devoted to workers’ causes; stylistically, she was a surrealist, perhaps the consequence of visiting Paris in 1937, just before the War. But her output includes both abstract and figurative art, sometimes with the two genres mixed together in the same painting. Even so, it is fair to describe her as a surrealist, that is, someone given to an idiosyncratic abstraction. There is also, in the show, a series of children’s images from a fairy tale that tells the whimsical story of an intrepid snail, a project likely in response to the birth of a son after the War. Surrealism, a European movement that started in the interim between the two world wars, allowed Rosenstein to work out a varied body of work, intensified by a strong sense of color and an original notion of composition. Still, her oeuvre is pretty much a homemade production; one does not sense the influence of the French or other major producers of surrealist art. Instead, the work often feels personal, not so much distilled through the terrible events she endured but, instead, expressing a private vision extreme in its originality.

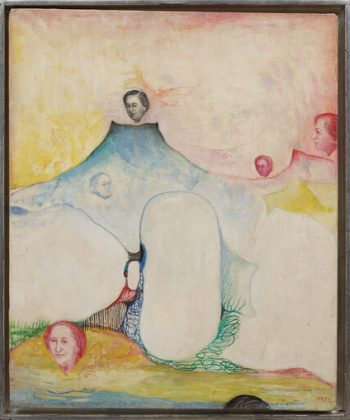

Surrealism, considered by most to be a product of unconscious processes, was both Freudian and figurative. It might be hyperrealist, as in the case of Salvador Dali, or sometimes, it could be abstract, as happens in the art of Yves Tanguy. But mostly it was a hallucination of reality, in which the everyday took on exquisitely detailed significance, as if the scenario being depicted actually existed in real life. This is of course untrue, as the art represented a willful withdrawal from the usual by envisioning a world in which the psychological impact of discrete objects took over the rendering of the objects themselves. In the case of Rosenstein, we see a broad array of figurative and abstract images, in which an everyday object, for example an empty paper case for cigarettes, might be embellished by an image of a pair of lips on the front. The striking discontinuity of the image embossed on the cigarette pack is a vision devoted to surrealist eccentricity–memorable for its strange conjunction of object and picture. Other images, such as the colorful landscape Afterglow (1968), a multi-hued painting with a cloudscape, a body of bright blue water in the middle, and a brownish landscape in the foreground, are more figuratively recognizable. While it may have been true that Rosenstein was mostly a surrealist, the figurative was never far out of reach in her body of work.

Besides surrealism, the other major factor encompassing Rosenstein’s work is her Jewish background. Her art is never religiously observant, but there is a strong sense of family in one of the figurative paintings, in which parents and other relatives are produced in groups in a single work of art. Having lost her parents in the horrific events of the Holocaust, Rosenstein was able to redouble her efforts toward a meaningful life by producing striking art that was eventually recognized within Poland but has been unknown here in America until now. When is art an act of resistance, and when it is an act of compromise? In the painter’s abstract work, it is difficult to attach a specific political meaning, but that does not entirely exclude a social stance. Perhaps the simple act of chronicling persons related to her is a means of keeping her culture alive by the act of memory. Closet (1960-2004), a wooden wardrobe whose glass windows are covered with pictures and other assemblage elements, looks very much like a piece of furniture the artist used at home. This domestic object, shown in the exhibition, can be considered an actual relic of Rosenstein’s life, presenting us with an artifact that would reify a comfortable daily life–not something she would have enjoyed during the years of the war. But this very personal body of work is only a small part of the show, even as its demonstrates the artist’s willingness to make public private aspects of her life.

In a show like this, we are resurrecting work from the past in order to establish the reputation of an underrecognized artist. In New York, the effort to bring into the mainstream artists who lived on the periphery is being constantly addressed. By now, surrealism is of course a historical movement. But at all times, there are the celebrities and those who remain mostly unknown. Rosenstein did get recognition in her native Poland, in part because she is very good and in part because the terrible story of her parents’ loss cannot be separated from her work, even if much of it is abstract. Indeed, Technical Motion (1985), an entirely nonobjective painting with an abstract title, indicates how several horizontal brown rods, and one vertical joining them against a gray background, has no figurative aspect at all. So it is clear that Rosenstein was more than effective in her abstract painting skills. This show, titled “Once Upon a Time,” conveys both a sense of the personal and a sense of the impersonal in deep ways. It is too soon to speak of the extent of her importance within the history of European surrealism–the work is not well enough known–but it is fair to remark on her abilities both as someone recording the private life of her past and the more public body of work that ties in with art historical sources.

Most interestingly, after the War, Rosenstein remained in Poland; one might well imagine that the artist would have left and re-established a life in a country far away from the events she endured. But she stayed. Doing so gave her art an integrity of place and theme that exiles could not match. While her work belongs to surrealism’s larger European existence, her decision to remain local in the country of her origin, and where she endured considerable suffering, gives her work a slightly marginal cast. Surrealism’s psychological bias and extravagant visual effects tend to push work belonging to it toward an eccentricity whose imagery is both recognizable and beyond belief. Dawn (Portrait of the Artist’s Father) (1979) is both personal and idiosyncratic in the surrealist manner. The painting depicts her father with a severed head; his demeanor is serious, and he is of considerable age–balding, with white hair and a white moustache. The head hovers in open space, toward the left of the painting. He is clothed in a blue suit and a black tie that would give him a sense of respectability–were it not for the fact that his head has been removed from his body! But the face is fully alive; there is no evidence that we are looking at a dead person. This mixture of a private view with an image process that subtly, or not so subtly, undermines the realism we come across describes Rosenstein’s efforts well.

Monuments (1956) presents three tall thin poles ending in faces–at least this is clear in the foremost monument. They occur in an orange-red sky, at the bottom of which is a low landscape painted in yellow. The foreground is taken up by three horizontal lengths of blue and gray, separated by the shadows thrown by the tall poles. Done only a decade after the Second World War, the image is stark and not without a sense of oblivion and emptiness. Who is being monumentalized in this work of art? There is no sign of political or social specificity that would explain its existential meaning. Instead, the scene takes place in a visual desert, without anyone or anything to contextualize what we see. How can monuments, meant to acknowledge the achievements of people, exist without irony or loss of meaning following the Holocaust? The head on the first pole wears an odd expression of worry or whimsical discomfort. It is hardly heroic in nature. The painting is in fact a tribute to the anti-monument, in which memory is reduced to something disturbing and absurd, rather than being a tribute to greatness. So this is a work in which the implications of war are reduced to something less than tragic–becoming a mere shadow of events that affected the artist so deeply. We can say that the painting is surreal in its refusal to memorialize, in any distinguished fashion, the tragedies of the past.

Generally, when we look at Rosenstein’s art, we see a mixture of pathos and formalist distinction. She is not someone who worked in series; rather, she engages in single projects in which her life often (but not always) merges with a style distant from herself, slightly unreal. A good example is Lips (1989), which presents only a pair of lips reddened by lipstick and surrounded by a layer of flesh-colored paint. Otherwise, the background, which takes up most of the picture, is dark. But the most telling detail of the work is the fact that the lips have been sewn together by black thread. This is a surreal detail, of course; but it surely has an allegorical meaning. What would the image mean in 1989? It must stand for the inability to say what we think, either in contemporary terms or, more generally, in political circumstances that refuse criticism of any kind. It is easy to invest surrealism with a symbolic aspect, as its style encourages the artist to expand upon a realist view in favor of strange, but also emblematic, details. Surely, this is not an idiosyncratic view only of a pair of sutured lips; it is also a demonstration, in very clear terms, of censorship. The image may well refer to the communist presence in Poland. Like all of Rosenstein’s work, it cannot be taken lightly, given that the implications of her art are as at least as important as the art itself. Because we know the terrible details of the death of her parents, we tend to see her work in light of that knowledge. This is someone whose life story cannot be separated from her work.

In the collage It Still Watches (1991), a single huge eye dominates the space of the work. The eye has a brown iris, and large, long eyelashes surround it. The bottom is a complex mixture of green and brown, unrecognizable forms. But the title suggests more than a simply surrealist study of an eye. Most of the time it is difficult to be precise about one’s critique of an authoritarian government, or an atmosphere in which opinions are quick to be attacked. Perhaps in the political maelstrom in which Russian-led communist fell apart, Rosenstein is commenting on the closely watched disagreement that took place at the time. Here surrealism merges not with the personal but with the political and the social, offering us imagery that eloquently addresses our constraints. Painted decades after the Nazis, It Still Watches might best be seen as a warning to its audience that we are being closely overseen in light of our thinking. This is of course a speculation, but given the symbolic significance of surrealism in general and Rosenstein’s interpretations of the movement in particular, we must read the painting as an expression of something larger than itself. Also, the problem of public expression continues to this day. Given the authoritarian cast of many governments now in power, it makes sense to read a thirty-year-old artwork as having a visionary, futuristic implication.

Maybe the clearest evidence of Rosenstein’s penchant for merging the personal with the symbolic is the painting Separate Season (1971). In this work we find four heads of an older woman, presumably a relative or, likely, Rosenstein herself, scattered among large rocks–on top of what looks like a volcanic peak, on grass at the bottom of the painting, and two heads off to the right. The irrational content of the painting poses a conundrum: what exactly does it mean? Sometimes, especially with surrealist art, there is simply no identifiable meaning, only the unexplainable juxtaposition of disparate images. Why should a painting always make sense? Ever since the early 1900s, with the beginnings of cubism, art has moved away from the conventional truth of perspective toward an active exploration of content not beholden to detailed figurative imitation. In this painting, though, the imagery is real enough–but the side-by-side occurrence of disembodied heads and stone formations is inherently unreasonable. So much so, it is hard to unravel the meaning of the picture. Part of surrealism’s freedom is that anything can be incorporated into a single work. So Rosenstein may not, at least in this painting, be offering us hidden personal or social meaning.

Clearance (1968) is, on the face of it, a completely abstract work of art with an abstract title. It looks fully apocalyptic in its expression: in the upper third, a series of white lines extending vertically with a triangular golden form in the center; then, in the middle, a series of horizontal forms, maroon-red and green-blue, acting as a foundation for the white wings; and, finally, toward the bottom of the painting, two brown, inchoate, horizontal tubular shapes on the right, and on the left, a mass of tubular layers of maroon that move upward on the side of the painting. There is some lack of clarity in the painting, but generally it seems to be exploring the notion of an upward ascension. One of the more positive aspects of Rosenstein’s work is its independent motivation from painting to painting. There is no sense of sequential exploration; each work of art survives on its own terms. In this particular case, Clearance suggests an abstract spirituality, as implied by its name. Spiritual deliverance is often indicated by a rising movement, and this painting looks very much like it is illustrating exactly that. When we consider the body of work experienced in this show, there is an implied–not an exact–merger between the artist’s personal life, her commitment to a surrealist esthetic, and an interest in the social and the spiritual. These concomitant themes make her a painter of true interest, whose perceptions range across a very wide field.

It is particularly interesting to see this work at this moment in time. Rosenstein’s art gives us a window into a career pursued despite the horrible events of her earlier life. Remarkably, she never left the country where her tragedies occurred. Instead, she stayed and pursued the style she came across when she was young. Her politics, not so openly evident in her work, belong to a time when the European Jewish intelligentsia was committed to Marxism. Living as long as she did, Rosenstein still managed to remain faithful to her compelling combinations of style. Likely, now, it is too soon to give voice to an evaluation of the permanence of her career. Moreover, she is one of those artists whose life events, fortunately or unfortunately, cannot be separated from our examination of her work. This is interesting because in the show nothing overt regarding the Holocaust is evident. Instead, we might assert that a sense of dislocation often occurs in the work. One assumes that this is partly a result of the surrealist style and partly a result of experience. Often art directly concerning the visuals of the Holocaust–for example, pictures of the concentration camps–suffer from a literalism despite their pathos. Rosenstein found a way of communicating the unreality of things even as she worked with recognizable imagery. We can only admire, truly admire, the consequences of work done despite the trials and tribulations of the artist. Rosenstein thus is an artist not only of striking visual imagery but also one of emotional truth in the face of totalitarian experience. Her work has a depth beyond much of what we see, then and now.

Texto en Español