Gertrude Goldschmidt, known to the international art world as Gego, was a Jewish art student who studied design and architecture as a young person in Germany (she was born in Hamburg). Her period of study lasted six years, from 1932 to 1938, at the Technische Hochschule in Stuttgart. But by then danger from the Nazi movement was heavily evident, and Gego moved to Caracas in 1939. Only in the 1950s did Gego start producing art for the public. An abstractionist of extraordinary gifts, the artist usually took wire and created outstandingly improvised inventions that were shaped by inspired use of the thin metal strands,, apparently her favorite material. Her creativity was evident both in the airy, regularly geometric forms created by the wire and by the gifted use of the wire itself. In the construction not only of the object but also the space it contained, the artist’s open cpnstructions resulted in a merger, in which line and volume fused, supporting each other. Grgo, trained in architectural studies, also would fill entire rooms with her filigree objects, activating dimensions by joining sculptural invention with the structured emptiness of a simple room. At first unoccupied but then filled with viewers, the room became both a container for individual works and, in a larger sense, a sculptural presence on its own.

Perhaps the key to Gego’s achievement lies in her ability to walk a tightrope between the linear structure of the wire, joined in ways that would free space for the viewer looking into the emptiness shaped by the wire’s form, and the more involved presentation of the works in conjunction with architectural space. One senses that Gego didn’t evade the problem between the sculptural space, so central to her work, and the linear design defining it. She never turned her back on the sculptural properties of architecture, even if that quality was not central to her style. It can be said that sculpture maintains close ties to architecture, just as the reverse is true. Both arts claim their presence through volumetric space. It must have happened that the artist’s visual intelligence was particularly strong in finding affinities in the two genres of art, establishing sculptural form into something to be looked at (as it always had been) rather than be occupied. If considered carefully, architectural space will yield sculptural features, in the sense the inhabitant moves through the room. It should not be overly emphasized, but Gego’s sculptures often indicate architectural influence–even as they remain clear examples of three-dimensional art. New technologies have pushed this tendency further; for example, Frank Gerhry’s work is well known for its sculptural presence, determined by computer design.

Yet we can hardly describe Gego as an architectural artist. Her wire sculptures capture interior space but are effectively considered as forms determined by volumetric space within a larger environment—open, empty air–rather than being experienced only as struts containing a shaped emptiness. We cannot force too close a connection between sculpture and the space buildings occupy, but the comparison can shed some insight on the complex interaction between the artist, the work of art, and the viewer.

Another way of looking at the works in this remarkable show is to see the forms as three-dimensional drawings, assembled in highly original ways. The work is thoroughly modernist and properly resides in the previous century’s innovations, when experimentation with form was a consequence of exploration achieved in the earlier part of the 20th century. Form was to be eradicated, or changed as much as possible. This was a central interest of many artists. So, at her frequent best, Gego, known more as a Venezuelan than a German artist, was able to construct a geographically neutral body of work that lived up to the remarkable creativity of her time. Her efforts, which took place entirely within the 20th century, reflect that time’s penchant for simplified constructions.

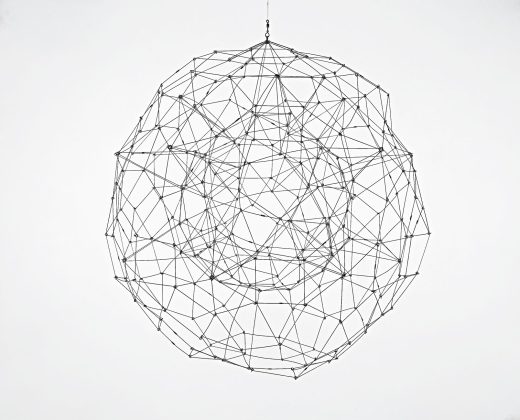

Esfera Nol. 4, a later work made in 1976, is a hanging: an open sphere built from short lengths of straight wire held together by small metal nubs. It is not so easy to see clearly, but there is another, smaller sphere, surrounded by the larger one. In both cases, the thin wire structure enables us to gaze through and beyond the form. Here it becomes necessary to make the most of highly reductive, minimal materials. Gego’s hand may seem simple, but it is not truly so. Instead, her sense of a simple constrution is made conceptually complex and visually intricate by repetitions of common materials. These materials, which we would easily pass over on the street, become the structure of elegant works of art.

Interestingly, Gego would sometimes make work tied to the perception of real things. In Bicho 87/89, an interesting, convoluted wire sculpture made in 1989, she created a form that folds over on itself. The word bicho means ”bug” in Spanish, and with the help of the title, that is exactly what the work looks like–an oversize insect A bit of imagining overtakes us: there is a simple, high oval crown at the top of the sculpture, and a dense amount of wire support at the bottom, beneath the head of the piece. At the same time, the work is an inspired abstract mass, composed of a loose conglomeration of metallic threads, issuing this way and that. We do think of Gego as an abstract artist, not a figurative one, so it is intriguing to read this intricate, complex work as the semblance of a bug. And despite the inevitable abstraction of Gego’s imagination, the construction does look like a bug. Additionally, materials are central to Gego’s undertakings. We start to appreciate the wire itself, which bends and straightens and climbs and falls according to the whim of the artist. A common hardware material is transformed, wonderfully, into art.

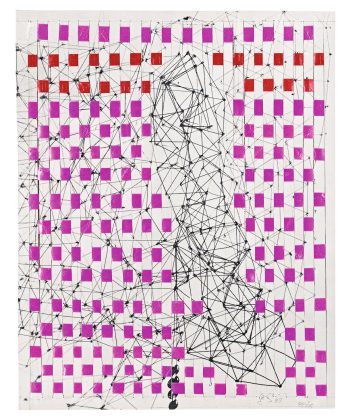

Gego was also highly gifted at drawing. In a late work from 1988, called Tejedura, the page of paper has regular rows of small purple squares. In the center of the piece is a a columnar wire-line drawing, closely evocative of the actual sculptural lines that constitute so many of the works Gego made. It is a beautifully drawn work of art, its linear complications offset by the rhythmic geometry of the squares. Perhaps one of the greatest achievements of modernism was its recognition that geometric form, in isolation from any suggestion of figurative art, would be of more than strong interest by itself. Gego understood the capacity of such a language from the start. It is clear that geometric form can occupy our full interest just by being itself, free of allusion–an insight central to abstraction as well as much art being made today. But Gego’s capacity for developing the innate beauty of abstract, linear form gave her an advantage–in the sense that the art established an attractive domain independent of recognizable visual meaning.

Even in her sculptural work, Gego tended to construct pieces that were drawings as much as they were volumetric forms. There is a tabletop sculpture from 1957 whose frontal emphasis pushes it in the direction of a drawing. Made of aluminum and paint, the work, entitled 12 circulos concentricos, consists of circles that express themselves in simple patterns: circular tubes of black metal closely follow each other, at the top and also at the bottom, where the curves rest on the pedestal. The elegance that results stems from Gego’s overall sense of design, as well as her ability to establish an unusual balance: the concentric circles, set next to each other in a repetitive manner, remain fixed as an abstract pattern. More than most artists, Gego indicates the possibilities, formal and also historically aware, of sculpture as an exciting chance for independent cohesion. She searches for beauty in ways that emphasize design and the materials they consist of. The wire works are, despite their linear construction, equally accomplished in their emphas on the development of space. Throughout the show, Gego shows us that less is more, making it clear that her penchant for simple gestalts does not limit her imagination in any way.

A particularly exciting work, Selva Jungle, from 1964, is a table-size sculpture whose structural elements are formally readable and abstractly oblique at once. Black rods (one is white) support some seven or eight images that suggest foliage; these rods are attached to a curving steel base. The base’s meandering line enabled Gego to create a fairly complicated environment consisting of steel forms whose embellishments were mostly rounded. The shapes are made up of thin horizontals extending outward, away from the rods to which they are attached. The piece hints at the dense cover we experience in a jungle, but on another level, the work is outstanding for its abstraction, lacking reference to things we know. It is true that Gego’s title directs us toward reading the sculpture as a simplified version of a jungle, but it is even more accurate to see its success as the result of discernible form in complex alignment with non-representational configuration. The tension that resulted is central to the way Gego worked.

Not only was Gego a highly gifted draftsman and sculptor, she was additionally a painter of distinction. In an untitled casein work created in 1956, Gego uses a stunning blue (and, slightly, green) as the background of her painting. Three vertical rows of hard-edge blue-white forms occur across the sky-like field, while shards of red, with sharp edges, cut across the middle of the painting and also the upper right. Some of us might view the painting as an inspired portrait of the sea. The light blue color of the painting is remarkably lyrical, although reading the work as a natural habitat seems a bit far-fetched. Instead, we can appreciate the work for its own, inherent qualities: an emphasis on color, made much more striking by the smaller, acutely edged forms moving up, down, and across the wall of blue. Their shape and hue create a meaningful emphasis, if not necessarily a recognizable one.

Writing about abstraction requires an approach that does justice to the style’s refusal to intimate realistic recognition. When abstraction in art came about, now more than one hundred years ago with the onset of cubism, the perception of form for its own sake was so new, it amounted to a revolutionary independence. But the idiom of words has leared to address the genre very effectively in a literary sense. Writing had to find a way of justifying the style with words. The writer has always needed to describe elements of visual expression on their own terms, in ways that kept the visual decisions alive. The abstract tradition is now firmly established for a number of decades, so we can assume someone like Gego would belong to a continuity. Thus, her achievements become, now, historically based even if they were avant-garde when they were made. When Gego worked, her tradition was not yet a tradition, except, perhaps, when it began to behave like one at the end of her career. But at the time she made her art, it was considered challenging and new. Her broad understanding of genres–sculpture, drawing, painting–allowed her to originate works that remain striking, perhaps the result of historical awareness and hindsight.

The remarkable steel-and-red paint sculpture called Quatro planos rojos, made in 1967, suggests that modernism functioned as a continuum for Gego. She borrowed aspects of abstraction that were prominent early on in its history, when the century was beginning. But Gego transformed early abstraction into her own outlook, which was visionary and idiosyncratic. This piece looks a lot like it came out of constructivism, successfully active as a movement more than half a century before Gego made her piece. What happens when a style is international, not regional, in scope? Do we lose the strengths of a specific culture? Doesn’t a monoculture reject particulars in favor of broad outlines that yield generalities alone? In the absence of difference, we must hope that an artist like Gego, who took the internationalism of her time and made it her own, was confidently addressing a lack of boundaries in her art.

The worldwide aspect of art we currently face results in questions that still have validity–even if they have been repeated for some time. Is Gego’s art German? Is it Venezuelan? If it is one or the other , what does that mean? Likely, the question is no longer valid. Gego slipped effortlessly into the specific confines of a style she put to use without difficulty. Nonetheless, notions of craft still prevailed; it is just that they cannot be identified as belonging to a particular geography or culture. In a world lacking cultural specificity, visual art is now tied most strongly to popular culture. We have known this for a long time; technology and politics, more and more worldwide in their influence, take up the conversation in ways that evade the particular elements of craft associated with good art. But it has not been determined whether popular culture can bring about permanent achievement when its constraints are so easily evident.

The four red, steel panels alluded to above extend from a center like leaves on a page of a book. It looks like all the panels have a circular hole in them; they appear to fold over each other as if stopped in the midst of a spinning motion.The pieces remind us of a slightly earlier time, when hard-edge geometry was favored. Gego’s ability to quote and then merge historical forms within the language of her time gave her art a depth one can feel even today. Looking at the show’s presentation, Gego’s audience might find it is difficult to chronicle the order of her art. She jumps from one style to another, and it is as if she was moving on all fronts at once. Abstraction may have been unprecedented when Gego began, but its long use made modernism a language distinctly established by the time the artist stopped working.

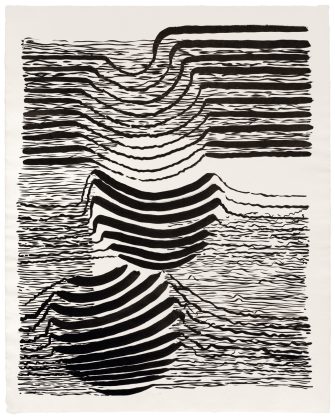

An untitled drawing, done with ink on paper in 1968, repeats curved forms that result in two spheres determined by rounded stripes, one on top of the other. The upper half of the upper sphere creates a semi-circular bulge by repeating lines that curve outward, horizontally extended but set on top of each other. Generally speaking, the middle area is lighter in tone. The line repetitions in this drawing, like a lot of Gego’s work, are light-hearted, although it is not easy to explain why. In this work on paper, as often happens in Gego’s art, the artist distances herself from a rigid approach. She shows interest across a broad array of possible styles. Working on paper suited Gego well; the drawings offer a mix of openness and control, aligning one way of seeing another. The balance of approaches reminds us that Gego’s art is both volatile and carefully set.

Gego did receive recognition, at the beginning of her career and later. As an artist of unusual accomplishment, she was active during a time of experiment with form. Interestingly, her work demonstrates both emotional restraint and an unaffected joyousness. Perhaps this is what happens when an artist takes on form for form’s sake alone; contradictions become formal supports. And despite Gego’s position as someone whose emigration had been forced, she did not direct her energies toward politics. Today in art, we are often weighed down by our attempts to change social mores. But Gego’s advances were visual rather than social or political. She participated in a time of remarkable exploration, free of outward influence. We have become so self-conscious in our social practice, we risk destroying the spirit of the object. Gego’s greatest gift was her lack of self-awareness, which resulted in the diffusion of joy. She made things because she wanted to, not because she wished to push forward an ideology. Her art, then, becomes a decades-long meditation on the shape of things, as well as the possibilities of materials, wire in particular. The results could not be more successful.

Texto en español