You come from a Russian and an East-European background. How did you end up in Buenos Aires? Did your Jewish background affect your desire to make art in any way?

I was born in 1929 in Argentina into a Russian and Romanian Jewish immigrant family. My maternal grandparents immigrated to Argentina before World War I to flee anti-Semitism in their native Russia. My father emigrated from Romania to Argentina for similar reasons. There he met my mother. They got married, and settled in Buenos Aires, where I was born. Perhaps indirectly my Jewish background had some influence in my desire to make art. Instinctively, I was looking for something that was rooted in an ancient tradition. Later in life I was unconsciously looking for that again in India, in Machu Picchu, and even eventually in France during a National Endowment for the Arts Residency when I visited the caves in Lascaux. One of the difficulties I experienced while growing up had to do with language: relatives who immigrated to Argentina fleeing anti-Semitism in their native Romania and came to live in our house, and didn’t speak Spanish, while I didn’t understand their language which was Yiddish. I myself took refuge in a church around the block from where we lived, searching for silence. Silence is a continuing refuge for me. I think that ever since, what language and silence meant to me became very important in my art.

Is there any art in your family? Did either of your parents practice art? Did they encourage you once you decided to become an artist?

There was no art in my family; no one practiced art or expressed any interest in it. My parents objected to my becoming an artist. They thought it was not the right profession for a woman, but they would go along with it if I also studied for a “real” career. We were living in Córdoba at the time. I enrolled in medical school, which I attended for a few years until I did quit in order to devote myself exclusively to art, which was my passion. I also became very interested and actively involved in politics and was a political prisoner under the military dictatorship of Juan Domingo Perón. Later I moved to Buenos Aires and then to Europe where I would live throughout the mid-late 1950s.

When did you know you wanted to be a painter? Did you study in Buenos Aires or in America, your eventual destination? How did your academic study affect your art?

I knew from the time I was an adolescent that I wanted to be an artist. My art has always been informed by an underlying fascination with the concealed aspects of existence that we don’t see, or that seem to be invisible. Through the processes I explore, I seek to reveal that which is concealed emerging into view. I try to make the invisible visible. This paradox has been central to my art practice and has been the essence of my artwork for the last sixty-five years. My art studies in Argentina began in Córdoba (1950-53) at the atelier of the Italian painter Ernesto Farina and later in Buenos Aires at the atelier of Héctor Basaldúa. I moved to Europe in 1956, where I continued my art studies at the University of Edinburgh, at La Sorbonne and at André Lhote’s atelier, both in Paris. Most significant was my exposure to the extraordinary art that I saw in the museums. Influenced by the School of Paris, my painting style became abstract and lyrical. Paintings from those formative years of my artistic development were exhibited in London, Edinburgh, and Copenhagen.

How and why did you come to America in 1967? Was this before or after the trips you took to the Southeast Asia? What did you take from your trips to places like India?

In 1967 I emigrated with my husband and our three children from Argentina to the United States for political reasons, settling down in Long Island. In 1987-88 I spent time in India, Nepal, and Indonesia. Exposure to these highly spiritual cultures had a profound impact on my work. I was able to observe Asian peoples in and around their temples, deeply connecting with what could not be seen or known. These encounters led me to explore aspects of existence which are neither visible nor tangible, but that may be known and experienced in a metaphorical darkness. My art making process is akin to the experience offered by many temples in India, where the gradual passage through various concentric walls —like the passage through layers in my work— finally leads to the literal dark of the innermost part of the temple which is called the sanctum sanctorum. Those ancient stone temples seemed to emerge from the earth, as if they were coming into view from concealment. I think that out of my profound and transformative experience of that year in Southeast Asia, a seed was planted in my mind that would have long-lasting reverberations in my future work. This includes my embracing stone with all its implications and connotations as a medium to make sculpture.

Your husband worked as a molecular biologist. Has science influenced the way you make art?

I don’t think so.

You made your way to New York in the late Sixties, the height of rebellious times, and have lived in America ever since. Yet your art is resolutely non-political —or at least not immediately visible. How did the Sixties make a difference in what you did?

Throughout my artistic career I have worked with a wide range of media, including drawing, collage, painting, sculpture and installation. I have been repeatedly drawn to spaces of silence and darkness in which my work can transcend its materiality, and where I can access a primordial source of ideas and inspiration. My artistic practice emerges from that source, and my art attempts to enact that emergence. I have been interested in what is my lifelong exploration of what I call the “dark source”. For me, embodied in this dark source are the concealed aspects of existence that lie behind the appearance of things, thoughts, language and the world. I was fascinated by the extraordinary art movements of the 1960s. Exposure to these art movements contributed to changes in my artistic approach. While I continued my exploration of the “dark source” my paintings, beginning with the series Dimension Five which I exhibited in 1973, became more refined and monochromatic. That year I became an American citizen. In 1979 I moved from Long Island to New York City. I resonated with and was influenced by Eastern philosophies, which led to my spiritual practice of Buddhist meditation.

How has living in the countryside, two hours north of New York City affected your work? Much of your work has to do with the land or the Hudson River, either technologically or for thematic reasons —for example, the rocks that are covered and then displayed by the high and low tides. Does your ecological life upstate sharply influence what you do?

Upon returning to New York City from my year- long stay in Southeast Asia, I realized that the slow process of incubation in my art practice was contrary to the fast pace of the art scene and the city itself. This awareness sparked my decision to move to the countryside, which I did, and I settled in the Hudson Valley. In the early 2000s I became interested in the exploration of nature’s modus operandi and its hidden processes in the context of rivers. Rivers change as they remain the same: while their waters constantly flow, their sediments accumulate layer upon layer. Emergences is a series of stone sculpture installations I created in site-specific locations along the shores of the Hudson River. They exist in a continual state of flux, being gradually concealed and revealed with the daily rising and falling of the river tides. They constantly emerge and submerge in and out of view. In my sculptures the layering of stones suggests geological and cultural time. They function as metaphors for the passage of time and for the ephemeral nature of existence. River Library is a series of drawings on handmade paper in which I use mud from rivers around the world as my drawing medium. Embodying the history of the earth and humankind, mud functions like the alphabet of a language yet to be deciphered, like a yet unwritten history of nature and culture, like a text that provides a memory of our existence: the drawing is the text and the text is the drawing.

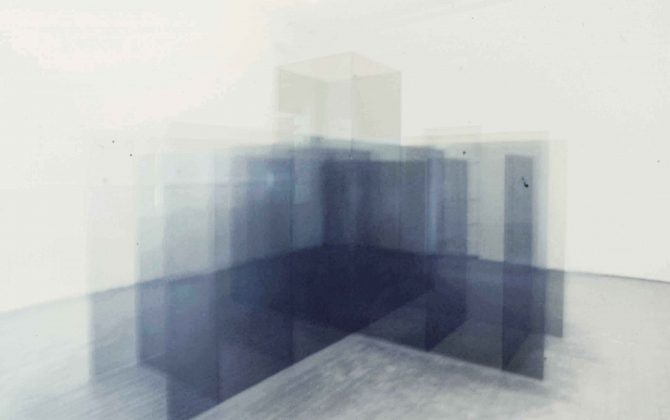

For a while you made elegant glass installations in the minimalist manner. Where and when did this happen? Do you describe this period in your career as minimalist? Why did you change your style?

There was a quality of transparency in the paintings I did during the 70s that awakened my interest in exploring glass as a medium for making sculptures and large site-specific sculpture installations. Glass emphasized transparency over solidity, invisibility over visibility while embracing permanence and impermanence, strength and fragility. Those glass environments I created in New York City during the 1980s in public spaces were for me immaterial: their materiality would disappear to become just transparency. Made out of tinted grey and tinted bronze glass panels in layered configurations, they invited the viewers to see from nothing to everything and from everything to nothing. Although my sculptures appeared to be minimalist, I think that in essence they were not. They were rather metaphors for spaces that were simultaneously accessible and inaccessible, open and enclosed, tangible and intangible, private and public, visible and invisible. Those glass environments referenced metaphysical, symbolic, architectural, and mathematical worlds. They were invitations to perceive new realms of meaning. I was interested in how the dark but transparent glass panels suggested spaces where reality and illusion intertwined in a continuous flow. They offered the viewers the opportunity to be at once observers and participants.

Spanish is your first language, and poetry means a great deal to you. Indeed, you have devoted yourself to a series memorializing major modern and contemporary poets. Please comment on why poetry is so important to you, and please give as examples two poets you pay homage to and how you do so visually.

My art is also informed by my love of poetry. For me art and poetry unfold from silence, from a space where thoughts are not yet articulated. My working process is like an excavation of that space from where poetry and art emerge. I’m working on an ongoing series of drawings which I call When Silence Becomes Poetry, dedicated to poets I love and feel deeply connected to. The drawings are not illustrations of poems, but rather my visual response to the language of poetry, a language which transcends the physicality of words. Some of the poets included in that series are Federico García Lorca, Rainer Maria Rilke, Jorge Luis Borges, St. John of the Cross, Pablo Neruda and T.S. Eliot. I work on many pieces at the same time. This is a slow process of unfolding, between intention and intuition, which in turn requires that the viewer experiences my work in a slowed down temporality.

Your series The Dark Is Light Enough comprises a group of paintings suggestive of roads, landscapes in light so dim they can hardly be seen. Is this a visual decision or a metaphorical one? Or both? What do you expect your audience to get from the series?

In 1961, upon my return to Buenos Aires after residing for many years in Europe, I began a long period of questioning which led to a series of new paintings. This series marked the beginning of a lifelong investigation into the nature of existence through the exploration of what I call the “dark source”. While working on them, I received in the mail from a friend in Paris a book entitled The Dark is Light Enough, by Christopher Fry. I was struck by the title and realizing that it perfectly embodied the meaning of my new paintings I decided that that should be their title. Being in Argentina where the language is Spanish, I wanted to find a poetic translation for it, but I couldn’t find it on my own. I went then to the Biblioteca Nacional in Buenos Aires where the director at the time was Jorge Luis Borges. I asked him whether he would translate it for me. He did; his translation was exquisitely poetic.

You left Argentina twice because of dictatorships. How close are you to the general Hispanic community in art, recognizing the fact that you have lived in America for more than fifty years? Do you remain imaginatively in contact with the South American tradition in art?

In many ways I come out of the Latin American world, of the artistic imagination, of a special way of thinking, which adds a layer over my Jewish heritage. I think I have a connection to the magical worlds in Latin American literature personified by writers such as Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez and Luisa Valenzuela. I resonate with those elements that are beyond the words, in between the lines, which are not literal. I have not been consciously aware of how that magical world would influence my art, of how important would become as an additional source for my work. I probably had a slight hint of it when painting the series entitled The Dark is Light Enough, which I have just mentioned. In fact, most of the paintings in that series were very dark. There is a difference between blackness and darkness. A dark place invites one to investigate, to dig in, to know more as it is difficult to see in the dark, both literally and metaphorically. It is a way of going deeper and deeper into dark places as a source of wisdom and knowledge. This is known in mythology. I did a series of drawings in 1998 in which text was embedded into the drawings, and in one of them the text was “If one can see in the dark, one can see everything”.

Please name two or three artists who are now working, whom you feel you have a relationship with stylistically. How do you feel about the genuine movement toward feminism in contemporary art?

I feel a connection, though not stylistically, with Jasper Johns, Wolfgang Laib, and Vija Celmins. Feminism has a very important place in contemporary art. Artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Ana Mendieta, Linda Montano, Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois and Hannah Wilke among others made extraordinary contributions toward it.

You are 91 years old. What do you want to do with the upcoming years in your work? Do older artists ever take a long rest from their work?

I want to keep on working until I die. As an older artist, speaking for myself, I do not want to take a long rest from my work and retire.