As an indigenous artist from the Flatland Indian Nation in Montana,, Jaune Quick-To-See Smith has been notably active in American art since the 1970s. Her position, as someone deeply cimmitted to the cultural preservation of of native peoples, is one in which she has felt compelled to present the historical visual culture of her background and, at the same time, critique the materialism and moral abandon that caused–and continues to cause–the genocidal harm that has so brutally damaged the tribes found in America. The artist’s works, which in the show included (mainly) paintings, works on paper, and sculptures, describe in contemporary terms the wide array of native imagery. The influence such imagery had on Smith’s own artistic idiom and politics has led to a body of work formidable in the specifics of her anger, but also accessible to a wide audience rather than taking on an academic bias. Thus, her style, neither esoteric nor overly simple, conveys very vividly the struggle of being an indigenous person today.

For an artist like Smith, born in 1940, both the period she lived through while young–the Vietnam War, the social engagements of the Sixties, the American Indian Movement (AIM)–along with her commitment to an engaged ar has resulted in work committed to a justice that continues to elude native peoples. Smith’s point of view would lead her to a visual assertiveness beyond the considerable strengths of her painting. Her decision to confront American material values, so much at odds with indigenous beliefs, has resulted in a style, mostly figurative, attacking the excesses of Western culture–its materialism, its psychological solipsism, its contempt for difference. Thus, Smith’s way of working, usually figurative, conveys the imagery of her culture, not only for its own sake, as an independent visual language, but as a marked alternative to European traditions.

How, then, does Smith convey the strengths of indigenous culture in a style that is both representational and hieratic? The artifacts of her people carry much more than functional meaning. fThe image of a canoe occurs often in these paintings, and there is a striking sculpture of a canoe, used to condemn America’s materialism by carrying used cans , painted a deep, flat red like the canoe, and filling the canoe’s seat. The very realistic sculpture, which presents the canoe in full-size actuality, pays homage to a boat essential for travel, but here, also, a carrier of American refuse. So the boat embodies an ethical judgment. Smith is critiquing our throwaway mentality, which has so deeply damaged the environment. As an artist well aware of the so-called “Western” orientation we are given to, in which objects for purchase become substitutes for feelings or ideas, Smith has been determined to condemn a predatory industry destroying the environment. The damage is a form of contempt; lands sacred to native peoples are exploited for oil drilling and destroyed. For a culture so closely connected to the landscape for so long a time, such an assault carries severe condemnation.

But Smith’s art opens a larger question, a theoretical one: How compelling can political art be, today in America? The museums, the audience visiting them, and the writers commenting on shows of indigenous can be facile in their easy judgment regarding the ongoing attacks on the culture, lands, and native general well-being by non-native peoples. Sadly, we are part of the problem even if we are not directly involved. Indigenous suffering, still overwhelming, may need someone like Smith to accurately illustrate the trouble following her people. She is painting pivotal works of art that respond to the aggression her people have endured for centuries. We must hope that her efforts, attractively painted and highly accurate in their description of a visual culture that has survived countless assaults, physical and metaphysical, do not weaken due to indifference and misunderstanding on the part of her audience–or from an easy agreement with the values being stated in the work.

Non-native people will easily recognize the wide range of imagery Smith uses. The objects include canoes, bison, masks, hieroglyphic images, and petroglyphs historical in origin, Smith’s style is improvisatory, a bit rough rather than refined. Her colorful style attempts a reckoning of an ancient tradition in light of modern times. While I have been emphasizing the political aspect of Smith’s efforts, the sharpness of her commentary would not be as telling without her accompanying strengths as an artist. Smith was trained by American art schools in contemporary times, so inevitably her art reflects her education to some degree. Yet she cannot completely follow the ego-expansive expressionism of the American manner. Her work is about nature and her culture’s place within it; her sensibility shows no evidence of the American glorification of self. Thus, Smith’s social position, given her life as an indigenous person, demonstrates a heightened awareness of difficulties we cannot easily share.

Smith is determined not only to participate in the developments of recent American painting; she is also merging the visual constructs of indigenous culture with current life. It is not an easy task. One of the terrible tragedies of native culture is the loss of native languages, replaced by English. This is a travesty–using the words of those who were bent on destroying you is a capitulation of the first order (but likely inevitable in contemporary life). Smith’s imagery has a life of its own: native headdresses, flint arrowheads, travois (sleds for heavy loads), the wide range of symbolic imagistic form– these artifacts and symbolic emblems cannot be erased.

So Smith transforms the confusion and living discards of a very great culture composed of many tribes, each with a particular language, their own narratives, and their own visual culture. Inevitably, the artist has had to simplify–the canoe she uses often carries considerable weight as image and symbol, without being anything more than a canoe. It is clear that the canoes keep their original function, as a vehicle of transport. This happens despite the images’ symbolic trappings, which support a real understanding of native life. So many artists in America are now of a culturally mixed background, it has become redundant to nvoke the intricacies of a complex inheritance as an inspiration. Yet Smith is trying to keep the mentality of indigenous thought alive, in full specificity–without the tragic element of cultural cooptation! She does this by emphasizing visuals that, through overuse, have become trite in popular American culture. Yet, for the artist, these pictorial means keep her outlook alive.

The beautiful work on paper, Petroglyph ParkI (1987), consists of mostly abstract effects: curved pink and white lines frame three triangles laid on top of a bright yellow background confined to the lower right corner. On the bottom left, a group of lines, straight black and blue zig-zags, partially cover a light blue sphere just to their right. Petroglyphs are most accurately described as rock art–incisions made on the face of stone. The abstract designs in Smith’s work show the influence of such art, which she renders with a sensitive creativity. In the upper left corner, a set of hieroglyphs come in–a horse and a sun are recognizable, if simply rendered.

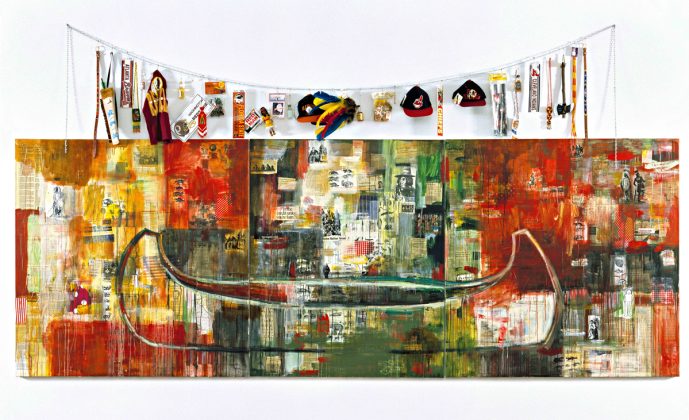

The key to Smith’s art lies in her ability to keep the language of her culture alive in a contemporary fashion. Her canoes, symbols of transport and evidence of a deep-seated continuity of physical culture, often are painted at the bottom of paintings that hold actual objects relevant to the artist’s background. The way in which these historical artifacts, some of them still used by native peoples today, are presented enables Smith to preserve her culture. Her commentary speaks to the eclectic truths of today–but from the vanatage point of grerat periods of time. This doesn’t mean that the art, consisting in this painting from influences millennia old, merely copies the past. There is nothing antiquated in Smith’s art. Instead, it bridges time and cultural history to offer as broad a statement as possible. Still, we must remember that Smith’s art is intended to preserve culture–and, likely, condemn the materialism eroding the traces of the past.

The “Petroglyph Park” series was made by Smith from 1985 through 1987. The works were done as part of an effort opposing a housing development in suburban Albuquerque, which would have destroyed petroglyphs in the area. How does a native person maintain opposition in the face of relentless development? Painting is a powerful tool, but its political strengths are politically limited. So its effect goes no farther than its visual expansiveness. As a political commentary–and such commentary is central to Smith’s esthetic–painting cannot hope to contain the damages resulting from the deeply harmful change imposed by the dominant white culture.

What can be cone? There is not much Smith can do beyond incorporating her culture within an attractive lyricism based on the visual contexts of her culture, old and new. In the excellent painting titled Herding (1987), mountainous peaks, shaped by jagged lines moving upward, downward, in every direction, create a many-colored tapestry. In the middle of the painting are horses, what look like coyotes,, and a tall, thin figure. The peaks are variously colored: blue, dark green, orange, white. The many muted colors used, along with the mixed orientation of the shapes, develop a metaphor in which the novelty of contemporary fine art is to a degree subdued by the ancient continuities of the landscape. The mountains, resulting from subtle changes over time, beyond measure, take their form from the subtle impact of the climate. Wind and water shape the landscape according to a chronology far too old to follow, while art occurs in the moment it is made–it is a marker of what has most recently occurred. Yet Smith finds a gravitas in the past.

The resurrection and then the maintenance of native visual culture, whose importance is increasingly lost because of the chaos imposed by colonial cultures, are necessary beyond words. Smith’s politics regularly uses immediately readable artifacts such as the canoe. In Trade: Gifts for Trading with White People (1992), Smith has painted a canoe, an open emblem of indigenous culture, in a painting filled with reds that suggest a neo-expressionism Smith has been associated with, although the characterization may be mistaken. On the top of the painting, we find thirty-one found objects strung from a chain. The title reaches back to the sale of Manhattan, a very early example of trade with native people, by native people to the Dutch for trinkets worth some $24. Here Smith takes an ironic point of view–what else can she do, given the long history of indigenous economic vulnerability.

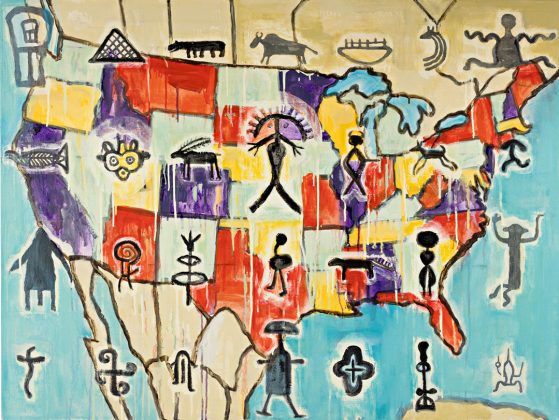

In Smith’s body of work, maps of the United States make frequent appearances. It is easy to forget, in heavily developed areas of America, that this land was once rural, the home of indigenous peoples rather than the scores of cultures we now find here. It becomes just as easy to forget that all of the land ascribed to the United States was once the property of indigenous tribes. Now reservations are found throughout the nation, but they are particularly numerous in the American West and Southwest. Smith’s maps represent a cogent assertion: the United States are a political organization, established by white people, of a land that does not belong to them. As happens so often in Smoth[s art, the image is a potent visual and a warning: America’s demarcation is arbitrary, and leads to hierarchies meant to keep life in constraint–according to rules not made by native peoples. Geographical partitioning is a severely politicized activity, and it looks like the division of all America, once entirely tribal lands, now occurs as a way of containing the far-reaching expanse of native holdings. These lands, of course, belong to native peoples.

As moving and powerful Smith’s evocations are, she can sometimes seem caught by the great burden of bearing witness to a diminished present and preserving the past in the same moment. Memory is key to survival. F or an artist such as Smith, her technical intelligence is always at the service of memory, its destructiveness influencing a people to whom history has not been kind. But even so fate-oriented an outlook ,the one we would agree on now, is merely tangential to the truth: indigenous history, which descrobes a long, slow attack on the economy and the culture, along with the political and social circumstances tribal members must deal with, tends to foster a troubled outlook. These difficulties don’t necessaruky demonstrate an inevitable enmity between native peoples and the dominant culture within which their lives take place. But it is troubling to see the advertisements for reservation casinos, which bring money to tribal nations but which also belong entirely to American pleasure culture. The point is that Smith has found it necessary to educate a culture that is erasing her own. Teaching the descendants of those who sought to destroy native peoples is a compromise Smith never should have been forced to make.

We are now in a time when, more and more, the agonies of native history are treated with some social awareness by dominant cultures. Only until recently did white culture take any responsibility for the destruction of much tribal culture. Beyond the ethics of the problem, the artist is faced with a great burden: How does a painter preserve what is already gone? The word “tragedy” is too rhetorical; it leads nowhere if native culture has been denied the means to transform their circumstances. It is not a word that accurately describes the devastation of indigenous lives. Native peoples’ political culture may have changed to a degree–the areas of contestation are no longer violent; the struggle has become more cultural, more abstract. Lawyers now replace warriors bearing bows and arrows. We must praise Smith for her originality; using the images and objects of her background, the painter rebuilds what has been torn down. This is hardly tragic! Native peoples understand thoroughly well what they are up against. Some of the struggle is linguistic; many of their native tongues are close to extinction.

The only alternative Smith has is to resist the contempt and technical dominance of America’s manstream. Yet her outlook is not especially hostile; her art is more supportive of indigenous culture than condemnatory of white interventions. Smith is determined to keep indigenous image-making and social exchanges alive. Her visual language revives properties of a tribal past in ways that continue the greatness of her tradition.Of course, viewers meet with anger in Smith’s work, but the emphasis is on a past that endures rather than failing to survive.

In Smith’s fierce and moving paintingThe Vanishing American (1994), which depicts three native people wearing traditional clothing and a headdress, the painter comes close to literally re-populating a vanishing people. The loss is more than a disappearance of a person; it is also the substitution of one kind of mentality with another. Sadly, it is close to impossible to evade the monoculture that has taken over nearly everywhere. The casinos on reservations exemplify such change. In a work more racially assertive than many in the show, Smith paints the native people with very reddish skin–a proud assertion of tribal identity. The three warriors are dressed for ceremony, or battle. The men are placed together closely, as if massed to defend themselves. They communicate an assertiveness that feels close to violent; the attitude is necessary if they are to survive.

This review has concentrated on Smith’s political resistance, defined through her very strong use of cultural artifacts. But the visual ramifications of her art remain equally important. Her technique, vivid and emotionally evocative, must be recognized. Smith’s work is hardly traditional; her paintings use a language notable for its contemporary immediacy. Her colors are bright and catch the eye; her forms skillfully communicate her culture, not through precision but through approximations that keep the spirit of the objects alive.

It is hard to fully grasp the combination of assertion and mourning suggested by this show. The title of the exhibition. “Jaune Quick-To-See Smith: Memory Map,” indicates how she proceeds–by the recall of ideas, emotions, and events that would enable her tradition to endure. Smith’s maps, a vivid series of paintings of the United States, remind us of an imposed political organization. Non-native peoples remain guests on lands that have never been truly their own. Smith’s art, so committed to preserving the specificities of her culture, has consequences: a spirited resistance to prejudice and a celebration of indigenous mind. Her work keeps her people alive!

As for those belonging to the dominant culture, it is hard to feel great responsibility for events and attitudes that were unconsciously learned, being part of a social fabric we felt was true to experience. Yet the implications of our treatment of native peoples was genocidal–the word is not too extreme to use. Our attacks resulted from a faulty imagination, one Smith is trying to correct. Her vocabulary remains truthful to the origins of her culture; she remembers the bravery, and the understanding of nature, that accompanied tribal culture before it was so badly harmed. This is why memory is so important to her art practice. Without recall, the culture will not endure. This is true for all of us who turn our back on the past. But it is especially true for native culture, which has been attacked for centuries. The indigenous mind Smith is keeping alive will remain alive, so long as we have artists of her stature.

Texto en español