The artist Juan Sánchez is an established name in contemporary art. His Puerto Rican parents took part in the wave of immigration from the Island to the United States in the 1940s and ‘50s; Sánchez was born in Brooklyn and raised in New York, where he was educated in art at Cooper Union. Later, he received his MFA from Rutgers. Although the artist has been based in New York for many years–he is a professor of art at Hunter College–he remains closely tied to his Puerto Rican cultural legacy. His work, consisting of paintings, printmaking, and photography and video, has often been politically oriented; his paintings include photos of Latin American social heroes such as Che Guevara and Pedro Albizu Campos, an important initial supporter of Puerto Rican independence, who spent years in jail for his beliefs. Sánchez grew up during a time of fierce social and political upheaval, and he has remained true to his experience, even as he has been increasingly accepted by art’s mainstream. His oeuvre embodies questions of commitment, especially in regard to the tattered identity of Puerto Rico, which remain ongoing. So it is fair to see Sánchez, even in a relatively mature segment of his life and art, as a supporter of a place and culture that has been forcibly relegated to a marginal status. The political situation does not look like it will be solved soon, but the cultural productivity of an artist like Sánchez can be remarked upon and supported, as a way of identifying not only the output of a highly gifted artist but also the art of a sensibility that remains adamantly Latino. The art stands as an enterprise in independence, rather than succumbing to the blandishments of the dominant culture in which Sánchez works and lives.

At this moment in time, when events are yet again proving how deeply prejudicial the American fabric remains, it becomes more important than ever to record the artistic efforts of someone like Sánchez, who mediates his origins with the academic legacies he has been trained in (not to mention his visits to city museums and galleries). One of his great gifts is his refusal to incorporate any easy content into his art. But, even so, his work displays the graphic achievement that is traditionally a strength of Latino art, in Puerto Rico particularly. Sánchez’s collages, which introduce photos, usually with social content, into the composition, can be seen as part of his graphic inheritance. But they are also more than that, being an introduction to the colonial history that has beset Puerto Rico for a long time–thus, Sánchez works as a witness to a culture in need of greater recognition.

Cultural immersion is not easily achieved, nor is it always desirable. In fact, the United States is composed, happily or not so happily, of many mixed identities, whose psychic and artistic complexities and differences are starting to be regularly investigated. Sánchez is an early, and highly successful, proponent of an art that would be true to the concerted array of truths he has had to live with, not all of them positive. But the oppositions he has had to face, evident in his work, has made his vision stronger, more available as a public insight. It must be recognized that this Nuyorican artist cannot be seen as an American artist alone. He is as committed to the homeland of his family as much as he is active in New York.

At the same time, to see Sánchez only as a political prophet would not recognize the breadth of his achievement. He is capable of unusually moving passages of feeling–a linear heart surrounding a photograph of a baby, for example. Often, too, we see a cross in his work–while we do not know if the artist is an active Catholic, it is clear he accepts the role of Christianity in his culture. For those participating in the New York art world, the combination of political adamancy, strong feeling, and even religious allusion may stand outside the vaunted American attributes of abstraction and formalism and egoistic assertion, but this is an obvious mistake–indeed, Sánchez speaks quickly of his strong interest in abstract expressionism and, later, conceptual art.

One of the problems with abstraction is its inability to be specifically driven in a political sense–we associate the Russian movements of constructivism and suprematism as being in concert with radical thought, but there is very little in the work itself we can align with the particulars of a leftist outlook. Moreover, in contrast, Sánchez’s progressive notions are cultural as much as they are political or economical (although such points of view also clearly occur in his art). Rican/structions, the term invented by salsa musician Ray Barretto, can be seen as the origin of Sánchez’s commitment to the reconstruction of a culture traumatized but not necessarily damaged by a colonial past–or the continuing colonial present. Independence, cultural, social, economic, and political, is key to any Puerto Rican outlook that would refuse easy compromise in regard to the inherent strengths of its history–in all the meanings of that term.

The paintings themselves are marvelous multimedia presentations of a sensibility informed by the past and the present, by the cultural and the social, and by traditional and current formalities (figuration and abstraction). In the remarkable lithograph, photolithograph, and collage named Para Don Pedro (1992), Sánchez offers the viewer a notable image: in the center, a photographic reproduction of Campos, the voice for Puerto Rican independence, with a framing that depends on a commercial portrayal of Jesus in a red robe in the four corners of the composition. Swirling about Campos there exist many spirals, a symbol regularly used by the Taino, the indigenous people who inhabited Puerto Rico. Para Don Pedro is astonishingly powerful both as art and as social document, attesting to the early political insights in Sánchez’s efforts. Campos is revered as one of the first voices in favor of independence, and Sánchez rightly establishes him in surroundings of aboriginal and Catholic culture, for historical and spiritual reasons, respectively.

In another work, titled San Ernesto de la Higuera (2011), the composition is divided into two parts: the upper half shows a bright red cross surrounded by a blue circular line, against an abstract background of lines, circles, and filled, variously colored spheres. Beneath, flanking an image of the Virgin Mary on a pedestal, are twin images: the face and shirtless torso of Che Guevara in death. Given the title, Sánchez here presents Guevera as a major figure, indeed one of religious significance; he is refusing to hide his sympathies. Yet it is interesting that the religious imagery is as important in terms of its occupation of visual space, no small part of the composition, as the space taken by the two pictures of Che Guevara. Each imagery, interestingly enough, supports the other not only visually but thematically. It is fair to say that Guevara is seen as a martyr to his cause, with clearly religious, as well as political, overtones. He is a saint in no uncertain terms.

Rosa (2007), a complex work incorporating collagraph, photolithography, collage, and hand-coloring on homemade paper, presents a photographic image of Rosa Luxemburg, the early 20th century, Polish-born German marxist. She is framed by a six-pointed star, a reference to her Jewish background. Extending beyond the star is a group of blue spheres that look a lot like images of the world from a great distance–land masses are given as white. This composite image takes up the higher half of the composition; beneath is a photo of two arms with open hands, which extend toward each other, with a fair distance between them, on a dark, muddy ground. What does this mean? Does the gap between the arms indicate a failed socialist movement, with solidarity having been lost? Or does it indicate the chance that hands might be joined in political agreement? It is hard to say, but that is a major strength of the artist’s work: we are meant to puzzle over the implications of the pictures, in ways that emphasize social justice but also include a high awareness of eclectic ambiguity–in the best sense of the term. Rosa demonstrates a stance of sympathy for the politically engaged for which the artist is well known.

Sánchez’s gifts have regularly included a mastery of abstraction. As Gerhard Richter has shown for decades, there need not be a division between figurative and non-figurative art in the work of the same artist. Sánchez is a New York artist if not a painter belonging to the New York School. Yet any painter in New York cannot help but be influenced by the extraordinary ab-ex tradition established there in the middle of the last century; this is something the artist himself makes clear in conversation. The New York School’s innate expressiveness, given such major artists as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, would make it a compelling stylistic choice for Sánchez, who is an artist always close to emotion in his art. This bias is particularly moving because we are now living in an age of academicism and, at least for some of the artworld, a time of over-intellectualization. While we must acknowledge the drive toward an intellectual reading of culture and art in the present day, it is also true, as Sánchez consistently makes clear, that we go to art for emotional reasons primarily.

So Sánchez, who is interested in conceptual art, is regularly given to feeling as well as to ideas. This point needs to be recognized because today the New York artworld justifies a lot of art–indeed, a lot of political art–by virtue of abstract and indirect suggestion. Such an approach may make the work smart, but it does not make it available to a wide audience, which Sanchez likely would want, given his political position. Feeling and form are dominant in his point of view–traditional attributes of art he makes contemporary by virtue of personal depth and technical skill. We need to recognize and acknowledge the artist’s unusual abilities in both realism and non-objective art–a skill set that argues against a divide between the two kinds of work; abstract elements like the Taino motif have just as much importance as the figurative elements that regularly particularize Sánchez’s art in a social sense. There is a tradition for this; sometimes a body of work can embrace different valences in the same work–for example, it is possible to see Mark Rothko’s paintings as simplified landscapes in addition to being seen as abstract rectangles of color–passages of emotion alone. The key is not to box oneself in as an artist, and given the multiplicity of media Sánchez has engaged in, it makes sense to see him as a gifted practitioner of multiple meanings.

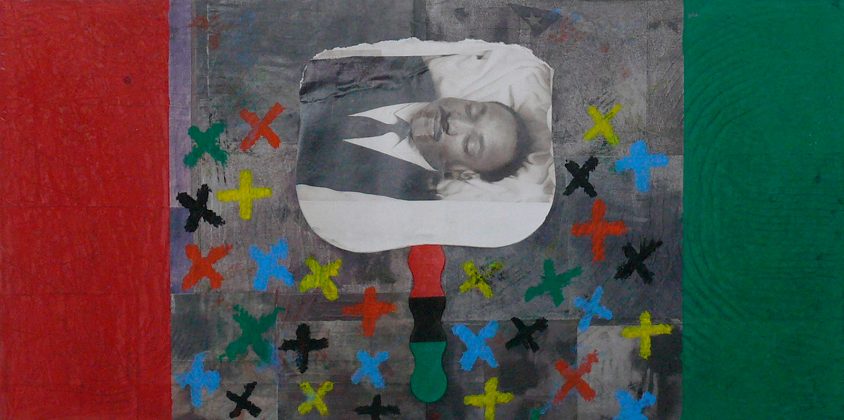

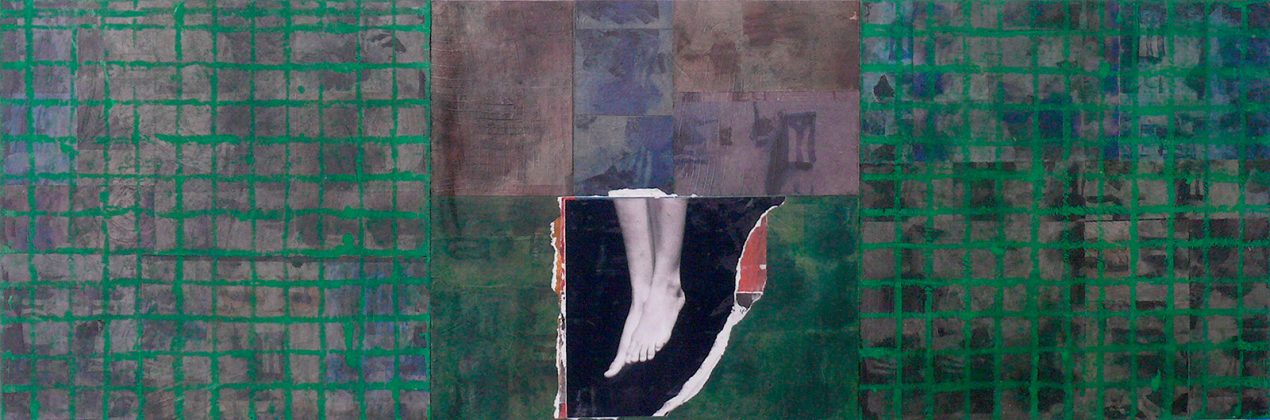

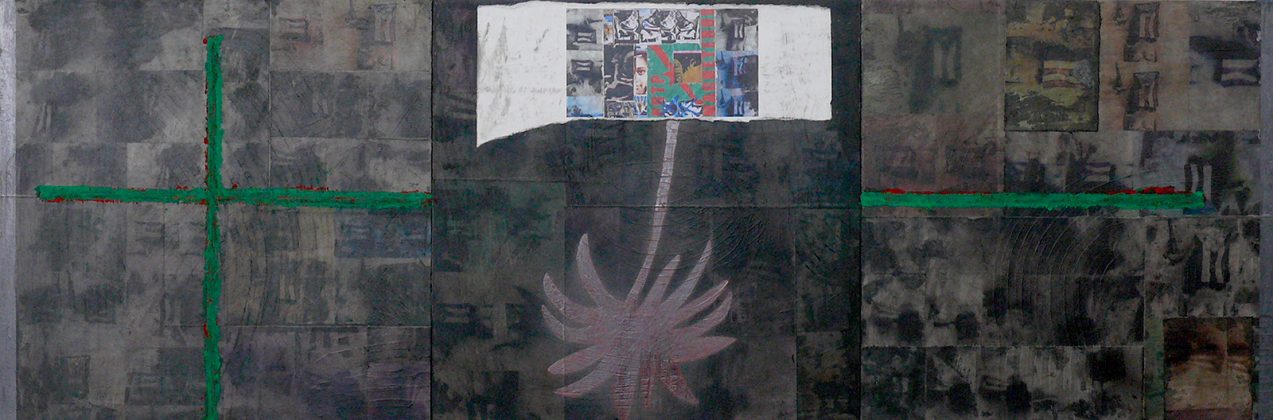

In his recent project, entitled “Fractured Grids,” a series of (as yet untitled) 12-inch-square panels, we can see the artist extend himself to those living on the Island and to those who make up the large Puerto Rican diaspora in America. There is a lot of excellent abstraction in these efforts, as well as a few startling realisms–one piece has a photograph of a nude, mud-covered Mendieta. Particularly interesting in this body of work is Sánchez’s compelling use of abstraction, simple passages of grays, collections of cross shapes, etc. in favor of a specific social reference. Here the artist makes good his double interest in the existence of a Puerto Rican people and their consequent American diaspora and the non-objective vernacular New York has traded in since before the middle of the last century. It can be said that these artworks feel like the culmination of years of working and thinking about how cultural and political insight might be enlivened and made strong by abstraction. My own feeling is that these panels are particularly strong as improvised signs of the persistence of the Island in New York, which has been a site of inhabitancy for Puerto Ricans for more than a century. Indeed, the strength of this work results from the elliptical connection made between the symbols Sánchez uses and the particular body of people he is referring to.

Now that Sánchez has approached a mature age, it is fair to ask how we can see the overall shape of his career. It is important to understand that he wears several hats–as a political artist, as a painter of considerable feeling, as a formal practitioner. His recognition as an artist is fully established. But in addition to our public awareness of his work, we need to know his art in all its different aspects. His excellent technical abilities are matched by an adherence to themes tied to his life rather than being only formal explorations. This gives his art the emotional immediacy that it possesses. It also shows that Sánchez is an artist who moves through the past, socially and artistically, to address an artistic present that he himself has been instrumental in making over the course of decades. This means that he is Rican/structing a reality that has been made tenuous by a long period of colonial exploitation. It is remarkable to see the extent to which his sense of the poetic has escaped colonial design.

It is likely that Sánchez has been able to evade patterns of social constraint by focusing, from the start of his career, on the political aspects of his background. He has done so without rhetorical excess, deliberating instead on a progressive sense of social and economic justice: what committed Puerto Rican artist would not do so? But this emphasis has not limited his explorations of art; there is a tenderness of feeling, along with an awareness of a Catholic presence, that accompanies his examination of Puerto Rican culture. Additionally, there is in his painting a movement toward pure abstraction that makes his current position as an artist complexly varied. We must see Sánchez as more than adept in his several kinds of art, which communicate intelligence and resolve on a high level. Images involving or devoted to his wife indicate the support of women, just as his portrait of the woman revolutionary Rosa does. The mixed-media piece incorporating a photo image of the late Ana Mendieta, unclothed, covered in mud, with a picture of roots beneath her, memorializes the tragic end of a gifted performance artist and sculptor. The sculptor and installation artist Pepon Osorio, born the same year as Sánchez was in Puerto Rico, is a colleague and friend; his intricate works support many of Sánchez’s themes. Also, the work of Rupert Garcia has been an important connection. As important as it is to recognize the politicized quality of much of the artist’s work, we must also underscore his abilities as an artist for whom feeling and form are primary vehicles. Once we join the different paths that Sánchez has taken, something that can be done convincingly, we begin to see him as a unified artist, for whom the public, the private, and the devotional are all of a piece.