The now-mature Russian painter Wilhelm Shenrok has had a strong academic career in Russia, where he continues to live. His work reflects his wide knowledge of Western art history, and is at the same time infused with an often direct eroticism that is very much his own vision, being at a distance from, if not at odds with, such artists and art as he imitates in his paintings: Renoir, Modigliani, Van Gogh, and examples of classical and surreal esthetics. As much a visual archivist and historian as a highly skilled, classically trained painter and draftsman, Shenrok moves in the direction of an appreciation that is both conventional and quirky. The sexualized nature of much of what he does should not be questioned–there is a considerable historical model for erotic expression in fine art–but must also be understood in light of contemporary culture, with its predilection for unabashed sexual presentation–this despite the fact that such work has traditionally been on the edge of the spectrum of what we usually see. But with the saturation of sexuality in culture worldwide–the result not so much of intimate feeling but of the need to parade desire as an act of self–Shenrok’s work is full in keeping with our current wish to keep sex open and accessible, without commenting on the question of its more visually elusive precedents, as well the notion that such art can be understood as necessarily marginal, even in an ethical sense. This may, or may not be a problem for those looking at Shenrok’s body of work, which has become as eclectic in recent years as it is technically accomplished.

No matter what we may think about Shenrok’s transparent promulgation of eros, it must be said that, as a biological drive, the wish for sex never leaves us. So there is a greater-than-cultural attraction to his work, which clearly examples sexual parts and fornication, across centuries and cultures, sometimes in the same picture, as the basis of support in his composition. Sexual directness in imagery is as old as Greek and Roman culture and earlier, as well as its existence in modernism, in which transparency of need is treated as a given, not as something to hide. Still, Shenrok is doing something new, and something provocative, when he invests the comparatively implicit eroticism of Renoir with something so unmediated as a finely detailed vulva in his imitation of the French artist’s portrait of a younger girl. Perhaps it is a matter of frankness and precision: Shenrok’s paintings belong both to a high cultural awareness and an unabashed enjoyment of sexuality, conventionally thought of as beyond the pale–at least in terms of propriety. It is impossible, though, to moralize about his use of abandon in his versions of art’s history–not only because we now live an age of secular ethics, in which desire is treated as regularly available to its representation as emotion, but also because Shenrok’s work is so very good at defining the interstice where history and physical need meet. Thus, we can only appreciate his talent in its demonstration of technical skill, even when his imagery stretches the boundaries of good taste. We remember that skill is an ethically neutral attribute in art; it is its use in service of a content we may not be comfortable with that provokes the desire to pass judgment on what is essentially a description of eros, an ethically impartial visual act.

Thus, for the reasons I have just commented on, the issues bring up are academic and moot. No one in the artworld–I assume worldwide–thinks hard anymore about these questions beyond the slight tremor of discomfort they may cause. If we think, for example, of Goya’s Nude Maja (ca. 1785-1800), surely a painting caused by and causing desire, Shenrok’s paintings can be understood as the continuation, in the second decade of the 21st century, of an erotic tradition firmly established in Western art. Still, the specificity of Shenrok’s art–its detailed descriptions of phallus and vulva–not only expand upon a tradition, they cross a line many have thought of as separating good taste from bad. Such considerations, though, are matters of opinion in an art world where notions of taste are now understood to be entirely personal rather than impartial notions of esthetic truth. Shenrok knows this in his bones, and his beautiful re-creations of imageries central to our appreciation of the past are provocative in part because he contemporizes them in his wish to simultaneously demythologize and eroticize art we know well. This does not mean that he is devaluing what he paints; indeed, the sense is that he loves what he is quoting. Yet his description of private parts–his art’s full frontal nudity–makes it clear that we are living in a time of indifference to privacy. There is certainly nothing wrong with this on an absolute level–change, in a progressive sense, may well be the engine of Shenrok’s style. But it can also be said that the eroticism is dulled by its very conspicuousness, which possibly puts his audience in an uncomfortable place.

Again, though, this is an hypothesis, one generated more from thinking about the art than viewing it. For most of us, the imagery is safely ensconced within a pronounced history of visual freedom, as well as the actuality of the recent past–in particular, the sexual revolution (now more limited to commercial uses!). The real question suggested by Shenrok’s art, namely, its ability to provoke desire within a conservative imagistic tradition, has been gone on for generations–think of Courbet’s painting, The Origin of the World, made in 1866, a century and a half before Shenrok’s current art: it is a detailed study of a woman’s vulva, placed in the foreground of the painting and presented with the directness of a still life. If desire is as old as life, and its stimuli are as old as art, we can hardly pronounce on the images as degenerate. Even so, we can think about, for a moment, the difference between eroticism and pornography, which seem to have recently merged in image-making. Is there truly a gap between the two? Is it a matter of coldness of perception, and if that is true, how do we measure coldness? And, finally, where does Shenrok’s portrayals of sex lie in the continuum proceeding from desire to eroticism to porn? It is a difficult and subtle question. These gradations are intuitive, and open to discussion, but responses to Shenrok’s art may well reveal viewers’ and writers’ own deep-seated attitudes toward eroticism. For many in Shenrok’s audience, sex is usually (but not always) thought of as a private matter.

But it is also a mistake to push Shenrok’s recent work entirely into the category of erotic art. His capacity for imitation, in the best sense of that word, is remarkable, and so his efforts may be seen just as much as an appropriation of art history that acts as an appreciation rather than as a theft. Given this painter’s unusual technical skill, it is fair to see him in light of our time’s elegiac, even mournful salute to artistic production before us, when the history of art had not seemingly been played out, necessitating an intellectual and political transformation of imagery and attitude (at least in America). Shenrok doesn’t reminisce so much as re-form what he loves in art into readings that convey both historical affection and the ageless desire for intimacy, although the latter has been given a contemporary twist. Historical conventions are just that–conventions need to be disrobed (quite literally in Shenrok’s vision), so their antiquated assumptions may be pushed ahead. This, we assume, is being done in a rational manner, given the artist’s predilection for precision and the mimicking of precedent styles. But sexualizing the imagery pushes us very much toward a place of irrational feeling; desire is hardly a construct of reason!

We can find examples of the dichotomy between imitation and erotic wish in almost all of Shenrok’s work. It is the key to his art. It occurs in a beautiful re-creation of a painting by Renoir of a youngish girl. In Violet Scent (1998), the girl sits wearing only a blue or violet hat or head scarf and a blue top; from her belly down, she is unclothed except for a blue stocking on her right leg, whose top alone we can see. Shenrok’s interpretation is clearly sexualized; the girl has the index finger of her left hand provocatively placed against her lips, while her erogenous attributes–her pubic hair and vaginal cleft–are impressionistically but undeniably present. As an example of sexual imagery, it is hardly a transgressive painting–we immediately remember, on looking at Violet Scent, that Renoir himself painted nudes of girls in their teens, whose attractiveness was only slightly diminished by his close-to-sentimental atmosphere. In Shenrok’s work, the sweetness of the portrait survives, with the added-on, perhaps somewhat unsettling, detail of a vulva freely available to his audience. Is this a soft embellishment or a hard erotic transformation of something that was, in Renoir’s painting, more delicately handled? It is hard to answer the question because erotic style is so much a matter of personal taste. Still, the bluntness of Shenrok’s image militates against a milder reading of desire; indeed, the coy sweetness of the girl’s expression tends to accentuate her physical attractiveness. So the eroticism is not suggested here so much as it is to be seen for what it is: the sex of a desirable young woman.

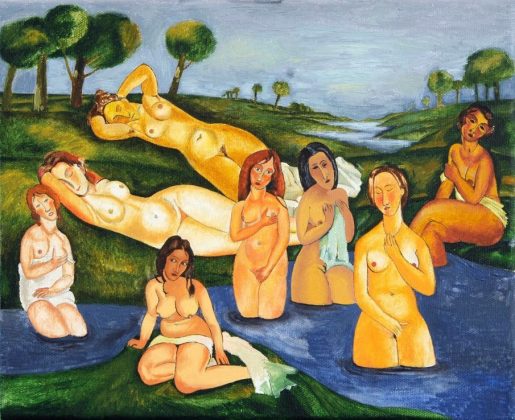

One hesitates to be so blunt, but the paintings demand candor. Not to speak of the painting above in the way that has been done would be to euphemize visuals begging for untrammeled report. A conscious erotic allure has often accompanied art, and is also a concomitant of human behavior, but Shenrok’s forthright depiction of desire calls renders things as they are. Even so, problems in his work can occur when his audacity crowds out subtle play–in both the image and its thematic content. In the painting called Large Bathers (2011), a large group of nudes, some eight naked women, half of them covered slightly by a cloth, sit, stand in, or lie alongside a small outdoor pond. In the background are a small number of trees with round domes of leaves, rising from low meadows on either side of a meandering river. The women are surely painted like Modigliani figures, but it is also true that the title and general landscape of the painting gives more than a nod to Cézanne’s great work, The Bathers, first shown in 1906. So Shenrok’s effort is ridden with historical allusion. It must not be dismissed, though, as a mere imitation. Its conjunction of the two artists is itself a creative act, while the painting is more than a re-presentation–it acts like an inspired melding of bodies and landscape, which is what it is. We do not have to be art historians to assert our awareness of Shenrok’s influences–first, because the influences are so easily available to see, and second, because the work of art succeeds in its own right. This is why Shenrok is both complicated and successful.

Great Love, Hope (2009) does not offer eroticism as a bridge between the artist and his audience. Instead, it presents a bare tree with different birds perched on its branches, while on either side of its trunk, Marilyn Monroe and Che Guevera feed bloodily on an avian creature. The title must be ironic, knowing as we do that Monroe committed suicide while Guevara was executed in what seems to have been a hopeless revolutionary mission in Bolivia. Irony is only a fraction of a step away from cynicism, and Shenrok’s dour portraits, based on photographic images of the two celebrities, seems to rule out both popular culture and revolt as legitimate states of mind. Monroe wears blue eyeliner and a brown cloth coat with a collar and sleeves embellished with lace, while Guevara looks somberly into the distance with his beret and multi-colored star pinned on its front. Eating the birds raw, both personae engage in a barbarous act, while the title underscores ironically the glory and optimism associated with the career of both before they died. These are public figures whose lives were played out in the limelight, and who embodied a more lyric, if not a more attainable, happiness and even grandeur of spirit. Shenrok seems to be mocking both American popular and populist culture, coming from the right; and Latin-American radicalism, coming from the left. The painter may be right in his estimate, but he leaves his audience nowhere to go. The cynicism is part of a current reading, not only American but worldwide, in which idealism and celebrity are always seen as corrupt behind the facade.

Maybe here Shenrok’s attitude can be criticized as being too derisive. Corruption, even if we recognize we are fallen, does not always accompany the idea, even if it regularly hovers in the shadows. Shenrok, like every artist making social points, has to face the implicit consequences of his own vision, in which art cannot sustain any sort of inspired outlook, either culturally or politically. This kind of thinking can be challenged, of course, but only after we have acknowledged it bears a certain truth, albeit one that lends small solace to those looking for inspiration from art. Monroe was popular but deeply self-destructive, while Guevera, also popular, died in what for many was a quixotic quest for economic change. Still, both were inspired, which is quite in opposition to society’s conventoinal recognition of their (and our) shaken condition. Utopianism or, on the other hand, a cynical view of our best intentions can carry us only so far; we are still in the grips of biology, established since the beginning of the species, not to mention the usually moderating influential effects of culture. Even if Monroe embraced materialism, and Guevera eschewed it, neither of the two were able to move beyond its grips, no matter the difference in their outlooks. Here Shenrok’s art records a nihilism made clear by their deliberate devouring of the birds, traditionally symbols of the spirit. In this case, not even the glories of art can save heroism from itself, at least in part because we are irrevocably damaged–fallen is likely the better word..

An earlier painting from 1982, called Philosopher’s Children, shows five naked Greek philosophers, two of which are deliberately statuesque, with their arms broken off, holding small children. The men are naked, as Greek men from archaic times would be. But there is no eroticism involved in the image–instead, the philosophers stoically support their young on their chest or shoulder. Like much of Shenrok’s work, the composition is allegorical, suffused with an emblematic reading of cultural effort. Beyond the surface of the image, the symbolic meaning seems easy enough to read; it is a depiction of the burden culture carries, determined as we are to perpetuate our beliefs and motives through the education of those following us. It is hard to say whether Shenrok is giving a fatalist or hopeful reading in this painting. The gray figures seem emotionally neutral, even should they also seem burdened by their offspring. Perhaps this is a painting describing the consequences of eros–the children, whose simple existence evidences the successful promulgation of desire, must be inculcated within Greek philosophy’s reason. But when has reason triumphed over desire? Only very, very rarely. The eroticism is entirely implicit in this painting, but it is nonetheless there, fueling the atmosphere of necessary responsibility the fathers bear toward their sons. Even if begetting young is, in the moment, an act of abandon, the results must be handled rationally. Education is the psychic opposite of erotic need.

In summary, art mediates the particular immediacy of desire and the generalized longevity of culture. Shenrok makes art about the gap separating the two, sometimes setting forth the strengths of one side, sometimes promoting the other. Art is both the bridge and the symbol of the gap between sensual need and the wish to create something lasting from its predilection for the moment. Maybe, though, the clash between both conditions is less pronounced than we think. Shenrok, who is an excellent artist, risks academicism in his close versions of art before him, but the sexualization of his imagery pushes toward a fevered re-interpretation of traditionally staid materials. This is an act of choice on his part, and it is partially an academic choice. But that does not limit his transformations. Instead, what we have is a revision of the past in contemporary erotic terms. Complications result once we have recognized that desire has supported the wish to create as long as we have been creating. Shenrok’s terms, direct in the extreme, may fail to completely transpose his copies into the world we now live in, but it is possible to discern in his work a real need to invest historical awareness with contemporary insight. It may be argued whether sexual feeling is the proper lens for viewing the past, but it is clear that we cannot dismiss its presence in our vision, especially now. As a painter, Shenrok makes it clear that the creative impulse, even the wish for historical appreciation, cannot be severed from appetite, even though we understand, sadly, that the latter is at least as strong as our need to transform it.